Table of Contents

World War I Explained: Causes, Alliances, and Global Aftermath

World War I stands as one of history’s most catastrophic and transformative conflicts, a war so devastating and consequential that contemporaries called it “the Great War” and “the war to end all wars”—descriptions that proved tragically optimistic. From July 28, 1914, when Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, through the armistice signed on November 11, 1918, this global conflagration consumed the lives of approximately 17 million people, wounded another 21 million, toppled four mighty empires, redrew the map of Europe and the Middle East, and fundamentally altered the trajectory of the twentieth century.

The war’s scale exceeded anything previously experienced in human history. Industrialized warfare—combining modern technology with mass mobilization—created killing fields of unprecedented horror. Soldiers huddled in muddy trenches stretching from the English Channel to the Swiss border, enduring artillery bombardments, machine-gun fire, poison gas attacks, and suicidal charges across no-man’s-land. Naval blockades starved civilian populations. Submarine warfare threatened global commerce. Entire generations of young men were decimated, leaving demographic scars visible for decades. The financial costs bankrupted nations and destabilized the global economy.

Yet World War I’s significance extends beyond immediate destruction. The war shattered the nineteenth-century European order built on dynastic legitimacy, imperial expansion, and balance-of-power diplomacy. It accelerated the decline of European global dominance while elevating the United States as emerging superpower. It created conditions enabling the Russian Revolution and Soviet communism’s rise. Its punitive peace settlement generated resentments that fueled fascism and contributed directly to World War II. It established patterns of total war, ideological conflict, and civilian targeting that characterized twentieth-century warfare. It transformed gender roles, labor relations, and state power in ways that shaped modern societies.

Understanding World War I requires examining the complex, interconnected causes that made war increasingly likely; the alliance systems and mobilization plans that transformed a Balkan crisis into global catastrophe; the military, political, and social dynamics of the war itself; and the profound, often tragic consequences that continue reverberating through contemporary geopolitics. This was not a war caused by simple factors or inevitable historical forces—it resulted from specific decisions made by political leaders operating within institutional constraints, cultural assumptions, and strategic calculations that, in retrospect, appear catastrophically misguided.

The Long-Term Causes of World War I

Historians have long debated World War I’s origins, proposing various explanatory frameworks. Some emphasize structural factors like the alliance system and arms races. Others focus on immediate triggers like the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. Most scholars now recognize that the war resulted from complex interactions among long-term trends creating a volatile international environment, medium-term crises heightening tensions, and short-term decisions transforming diplomatic crisis into military conflict.

Nationalism: The Ideology Reshaping Europe

Nationalism—the belief that people sharing ethnic, linguistic, or cultural identities should form sovereign political units—emerged as the nineteenth century’s most powerful political ideology, fundamentally challenging the multinational empires dominating Europe. French Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars had spread nationalist ideas across the continent. The 1848 revolutions, though largely unsuccessful, demonstrated nationalism’s mobilizing power. Italian and German unifications in the 1860s-1870s showed that nationalist movements could create powerful new states from fragmented territories.

By the early twentieth century, nationalism was transforming European politics in ways that destabilized the existing order. In the Balkans, South Slavic nationalism posed existential threats to the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Serbian nationalists envisioned uniting all South Slavs—including those in Austria-Hungary’s Bosnian and Croatian territories—into a greater Serbia or Yugoslavia. This “South Slav problem” created perpetual tension between Austria-Hungary (determined to suppress nationalist movements threatening imperial integrity) and Serbia (championing South Slav nationalism and enjoying Russian support as fellow Slavic nation).

The 1908 Bosnian Crisis, when Austria-Hungary annexed Bosnia-Herzegovina (which it had administered since 1878), enraged Serbian nationalists who considered Bosnia part of the South Slav homeland. Russia, humiliated by its inability to prevent the annexation, vowed not to back down in future Balkan crises—a commitment with catastrophic consequences in 1914. The Balkan Wars of 1912-1913, which saw Serbia nearly double its territory at Ottoman and Bulgarian expense, heightened Austrian fears of Serbian power and emboldened Serbian nationalists to pursue even more ambitious goals.

Pan-Slavism in Russia reinforced these dynamics. Russian nationalists viewed Russia as protector of Slavic peoples throughout Eastern Europe, creating cultural and political solidarity with Serbian nationalism. While Russian policymakers’ commitment to Pan-Slavism varied, it provided powerful ideological justification for supporting Serbia against Austria-Hungary—positioning Russia as defender of Slavic peoples against Germanic imperial oppression.

German nationalism took increasingly aggressive forms in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The unified German Empire, created through “blood and iron” rather than democratic movements, developed nationalism emphasizing military prowess, racial superiority, and great power status. Pan-German movements advocated expanding German territory and influence, viewing war as legitimate tool for national aggrandizement. This aggressive nationalism, encouraged by Kaiser Wilhelm II’s bombastic rhetoric about Germany’s “place in the sun,” alarmed neighboring nations and contributed to encirclement fears that shaped German strategic planning.

French revanchism—desire to recover Alsace-Lorraine lost to Germany in the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71)—sustained French hostility toward Germany. While most French leaders recognized that immediate war to recover lost territories was impractical, revanchist sentiment ensured that Franco-German reconciliation remained elusive and that France would eagerly support any coalition challenging German power.

Nationalism’s destabilizing effects extended beyond great powers. Irish nationalism challenged British control, creating domestic political crises that distracted British attention from continental affairs. Polish nationalism, directed against Russian, German, and Austrian rule simultaneously, complicated great power relations. Italian irredentism claimed Italian-speaking territories in Austria-Hungary, straining Austro-Italian relations despite their nominal alliance. These multiple nationalist tensions created an international environment where any crisis could trigger wider conflicts.

Militarism: The Culture of Armed Power

Militarism—the glorification of military values, the expansion of armed forces, and the conviction that military strength ensures security and international influence—pervaded early twentieth-century European culture and politics. This wasn’t simply pragmatic attention to military preparedness but a broader cultural phenomenon where military virtues, aesthetics, and thinking dominated public discourse.

The arms race, particularly the Anglo-German naval race, exemplified militaristic competition. Britain’s naval supremacy, maintained since Nelson’s Trafalgar victory (1805), was fundamental to British security and imperial control. The British “two-power standard”—maintaining a navy equal to the next two largest navies combined—had long ensured British dominance. When Germany, unified and industrially powerful, began building a modern battle fleet under Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz’s ambitious naval program (beginning 1898), Britain viewed this as existential threat.

The naval race consumed enormous resources and poisoned Anglo-German relations. Germany’s geographical position meant its fleet couldn’t challenge British commerce without first defeating the Royal Navy in battle—making the German fleet appear to British eyes as offensive weapon aimed at British security. Britain responded with accelerated naval construction, including the revolutionary HMS Dreadnought (1906), whose all-big-gun design rendered previous battleships obsolete and sparked new construction race. By 1914, Britain maintained clear naval superiority, but the race had transformed Germany from potential British partner into probable enemy.

Continental powers engaged in massive army expansion. France and Germany, expecting future war, maintained large conscript armies supported by extensive railway networks enabling rapid mobilization. The German army grew from approximately 400,000 in the 1870s to over 800,000 by 1914, while France, with smaller population, struggled to match German numbers by extending conscription length. Russia, despite its vast population, faced challenges modernizing and equipping its enormous but technologically backward army.

Militarism shaped popular culture and elite thinking. Military uniforms dominated aristocratic fashion. Martial music and patriotic songs celebrated military glory. School textbooks glorified national military heroes and historic victories. Military parades were major public spectacles. Veterans’ organizations wielded political influence. Dueling, though increasingly restricted, remained symbol of aristocratic honor culture where violence resolved disputes. This cultural militarism made war appear not as catastrophe to avoid but as test of national vitality and opportunity for heroic achievement.

The Schlieffen Plan epitomized how militarism shaped political decisions. Developed by German Chief of Staff Alfred von Schlieffen and modified by his successor Helmuth von Moltke (the Younger), this operational plan addressed Germany’s nightmare scenario: simultaneous war against France and Russia. The plan called for rapidly defeating France through massive attack through neutral Belgium while holding defensively against slower-mobilizing Russia, then shifting forces eastward to defeat Russia. The plan’s rigidity—requiring immediate mobilization and attack once activated—meant that military imperatives would drive political decisions. When crisis came in 1914, military leaders insisted that mobilization delays would doom the plan’s success, pressuring political leaders to act quickly rather than seeking diplomatic solutions.

Social Darwinism provided intellectual justification for militarism. Popular misapplications of Darwin’s evolutionary theory to international relations suggested that nations, like species, competed in struggle for survival where only the fittest prevailed. War wasn’t tragedy but natural selection mechanism strengthening nations and races. German historian Heinrich von Treitschke famously proclaimed that “war is not merely a necessary element in the life of nations, but an indispensable factor of culture.” Such thinking made preventive war seem rational—striking potential enemies before they grew stronger appeared prudent rather than aggressive.

Imperial Rivalries: The Scramble for Global Dominance

The late nineteenth-century “New Imperialism” saw European powers, Japan, and the United States scrambling to acquire colonial territories in Africa, Asia, and the Pacific. Between 1870 and 1914, European powers colonized virtually all of Africa, vast regions of Asia, and Pacific islands, creating global empires where the sun never set on European flags.

Colonial competition generated numerous international crises that could have triggered war. The 1898 Fashoda Crisis pitted Britain against France in Sudan, bringing two powers to brink of war over African territory. The two Moroccan Crises (1905-06 and 1911) saw Germany challenge French colonial ambitions in North Africa, testing alliance commitments and military preparedness. The 1908 Bosnian Crisis involved Austria-Hungary’s Balkan expansion. These crises were resolved through diplomacy, but they created precedents, tested alliances, and established patterns of brinkmanship.

Imperial competition reflected and reinforced great power rivalries. Britain, possessing the largest empire, pursued policies maintaining its colonial advantages while preventing rival powers from acquiring territories threatening British strategic interests. France, having lost territories to Germany in Europe, sought compensation through colonial expansion in Africa and Southeast Asia. Germany, unified late and arriving when most desirable territories were claimed, pursued aggressive colonial diplomacy seeking its “place in the sun”—colonies conferring great power status and providing resources, markets, and national prestige.

Russia’s expansion into Central Asia and pressure on Ottoman territories in the Balkans and Black Sea region represented imperialism’s continental variant. Russian ambitions to control the Turkish Straits (Bosphorus and Dardanelles)—crucial for Russian naval access and grain exports—created ongoing tension with Britain (which sought to preserve Ottoman Empire as barrier to Russian expansion) and Austria-Hungary (which competed with Russia for Balkan influence).

The economic dimension of imperialism was significant if sometimes exaggerated. Colonies provided raw materials for European industries: rubber from Congo, oil from Middle East, cotton from India, minerals from Africa. They offered markets for European manufactured goods and destinations for capital investment. European banks financed railways, ports, and resource extraction across colonial territories. However, whether colonial profits justified the enormous military and administrative costs of imperial maintenance remains debated—prestige and strategic considerations often mattered more than economic rationality.

Imperial competition fostered militarism and naval expansion. Protecting far-flung colonies and trade routes required powerful navies and global military presence. The British Empire’s security depended on naval dominance. Germany’s colonial ambitions required fleet to project power globally. France and Russia needed naval forces to protect their colonial interests. This connected colonial competition with military build-up, creating multiple friction points where imperial and military rivalries intersected.

Most importantly, imperial rivalries created international environment of competition, distrust, and zero-sum thinking where one power’s gain appeared as another’s loss. Diplomacy became continuous maneuvering for advantage. Any power’s colonial acquisition triggered demands for compensation from rivals to maintain balance. This competitive atmosphere made cooperation difficult and crisis resolution harder, contributing to the sense that major war was increasingly probable if not inevitable.

The Alliance System: Entangling Commitments

The alliance system dividing Europe into two armed camps—the Triple Alliance (Germany, Austria-Hungary, Italy) and Triple Entente (France, Russia, Britain)—transformed what might have remained localized Balkan conflict into continental and ultimately global war. Understanding how this system developed reveals how attempts to enhance security through alliances paradoxically increased war’s likelihood and scope.

Bismarck’s alliance system (1871-1890) initially aimed to isolate France and prevent formation of anti-German coalition. After defeating France in 1870-71, German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck sought to preserve German security through complex alliance networks. The Dual Alliance (1879) linked Germany with Austria-Hungary, committing mutual defense against Russia. The Three Emperors’ League (1881, renewed 1884) brought Russia into association with Germany and Austria-Hungary, though Austro-Russian Balkan rivalries made this unstable. The Triple Alliance (1882) added Italy, though Italy’s commitment remained questionable given Italian-Austrian tensions over Italian-speaking Habsburg territories.

Bismarck’s genius lay in maintaining multiple overlapping agreements that gave Germany central position in European diplomacy while keeping France isolated and potential enemies separated. However, this required skilled diplomatic management, flexibility, and willingness to limit German ambitions. Bismarck famously said Europe was a chessboard where Germany must keep three balls in the air simultaneously—managing relations with Austria-Hungary, Russia, and Britain required careful balancing.

Kaiser Wilhelm II’s “New Course” (post-1890) abandoned Bismarckian flexibility for aggressive foreign policy emphasizing German strength and demanding recognition of German great power status. Wilhelm II dismissed Bismarck in 1890 and allowed the Reinsurance Treaty with Russia to lapse, opening door for Franco-Russian alliance. The 1894 Franco-Russian Alliance created the nightmare scenario of German encirclement—potential two-front war that German military planning obsessed over. This alliance, combining French financial power and industrial capacity with Russian manpower and resources, fundamentally shifted European balance.

Britain’s “splendid isolation” ended as German power grew. Britain traditionally avoided permanent continental alliances, relying on naval power and balance-of-power diplomacy. However, German naval expansion, colonial rivalries, and aggressive diplomacy convinced British leaders that accommodation with France and Russia served British interests better than antagonizing them while Germany grew stronger. The 1904 Entente Cordiale with France resolved colonial disputes and established friendly relations. The 1907 Anglo-Russian Convention settled Asian territorial disputes. These agreements weren’t formal military alliances but created expectation of cooperation and diplomatic coordination.

The resulting alliance blocs created dangerous dynamics. First, crisis escalation became more likely because each power’s involvement potentially triggered alliance obligations. A conflict between Austria-Hungary and Serbia might require Russian intervention (supporting Serbia), which would activate German alliance with Austria-Hungary, triggering Franco-Russian alliance, potentially involving Britain supporting France. What began as Balkan dispute could cascade into continental war through alliance mechanics.

Second, alliance commitments reduced diplomatic flexibility. Powers couldn’t easily abandon allies without losing credibility and leaving themselves isolated. Austria-Hungary knew Germany would support it; Serbia counted on Russian backing; France and Russia relied on each other; Britain had moral if not legal commitments to France. These expectations locked powers into supporting allies even when prudent restraint might have prevented escalation.

Third, military planning assumed alliance support, making alliances self-fulfilling. German Schlieffen Plan assumed Austria-Hungary would tie down Russian forces in the east. French planning counted on Russian pressure forcing Germany to divide forces between fronts. Russian mobilization plans coordinated with French military needs. These integrated military plans meant that crisis management required coordinating multiple governments and militaries simultaneously—extremely difficult under time pressure.

Fourth, the alliance system created false sense of security among member states. Each side believed alliance strength deterred adversaries from attacking. Germany felt confident with Austrian support and Italian nominal alliance. France, Russia, and Britain believed their combined power prevented German aggression. This mutual deterrence appeared stable, but it meant that once war began, both sides expected their alliance strength to deliver victory—making them more willing to risk war than they might have been in isolation.

The Spark That Ignited the War

The complex, volatile international environment created by nationalism, militarism, imperialism, and rival alliances needed only a spark to ignite catastrophic conflagration. That spark came on June 28, 1914, in Sarajevo, Bosnia—but the assassination’s ability to trigger world war depended on the deeper structural conditions making the international system explosive.

The Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand

On June 28, 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, and his wife Sophie were assassinated in Sarajevo by Gavrilo Princip, a nineteen-year-old Bosnian Serb member of Young Bosnia, a revolutionary organization seeking South Slav liberation from Austrian rule. The assassination resulted from conspiracy involving Serbian nationalist organizations, particularly the Black Hand (a secret society of Serbian military officers), though the extent of Serbian government knowledge and approval remains debated.

The date was symbolically loaded—June 28 was Vidovdan (St. Vitus Day), commemorating the 1389 Battle of Kosovo where Ottoman forces defeated Serbian armies, ending medieval Serbian independence. For Serbian nationalists, the date symbolized Serbian suffering under foreign rule. Franz Ferdinand’s visit to Sarajevo on this date seemed deliberately provocative to South Slav nationalists.

The assassination itself was almost comedically bungled yet ultimately successful. Multiple conspirators positioned along the motorcade route were supposed to throw bombs or shoot the Archduke. The first bomb attempt failed, injuring spectators but missing the Archduke’s car. Franz Ferdinand insisted on continuing to the city hall, then visiting wounded spectators in the hospital. His driver took a wrong turn onto a street where Princip happened to be standing. When the driver stopped to reverse, Princip stepped forward and fired two shots from close range, mortally wounding both Franz Ferdinand and Sophie.

The assassination’s immediate impact was muted. Franz Ferdinand had been unpopular with Austro-Hungarian elites—his morganatic marriage to Sophie (a countess of insufficient rank) had caused scandal, and his political views advocating greater Slavic autonomy within the empire threatened Hungarian interests. Many in Vienna’s ruling circles felt little grief. European public opinion expressed sympathy but assumed crisis would be resolved diplomatically like previous Balkan incidents.

The July Crisis: From Assassination to World War

The five weeks between assassination and general war—the “July Crisis”—saw diplomatic failure, military imperatives overriding political caution, and miscalculation transforming local conflict into continental catastrophe. Understanding this crisis reveals how structural factors and individual decisions interacted to produce war.

Austria-Hungary faced a fundamental decision: accept the assassination and appear weak, encouraging further nationalist violence, or punish Serbia and risk Russian intervention. Austro-Hungarian leaders, particularly Chief of Staff Conrad von Hötzendorf and Foreign Minister Leopold Berchtold, concluded that the empire’s survival required crushing Serbian nationalism decisively. They believed that failure to respond aggressively would encourage nationalist movements throughout the multinational empire, potentially leading to imperial disintegration.

However, Austria-Hungary required German support to risk war with Serbia, as Russian intervention supporting Serbia seemed probable. On July 5-6, Austria-Hungary sought German backing—the crucial diplomatic moment of the entire crisis. Kaiser Wilhelm II and Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg issued the infamous “blank check,” assuring Austria-Hungary of German support regardless of consequences. This German commitment reflected calculations that war, if it came, was better fought now than later when Russia completed military modernization and Franco-Russian alliance grew stronger.

Austria-Hungary delivered an ultimatum to Serbia on July 23 with forty-eight-hour deadline—deliberately crafted to be unacceptable. The demands included suppressing anti-Austrian propaganda, dissolving nationalist organizations, arresting conspirators with Austrian officials participating in investigations on Serbian soil (violating Serbian sovereignty), and other conditions amounting to Serbian subordination to Austrian control. European leaders recognized the ultimatum as prelude to war rather than genuine diplomatic negotiation.

Serbia’s reply on July 25 accepted most demands but rejected Austrian participation in Serbian internal investigations as incompatible with sovereignty—a position gaining sympathy from Russia, France, and Britain. Austria-Hungary rejected the reply as insufficient and broke diplomatic relations, beginning mobilization against Serbia.

Russia faced its own critical decision. Would it support Serbia and risk war with Austria-Hungary and Germany, or abandon Serbia and lose credibility as Slavic protector? Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Sazonov and military leaders urged supporting Serbia, arguing that backing down again (as in 1908 Bosnian Crisis) would destroy Russian prestige and encourage further Austro-German aggression. Tsar Nicholas II, after initially hesitating, authorized partial mobilization against Austria-Hungary on July 28—the day Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia.

Germany’s Schlieffen Plan created inexorable pressure for rapid escalation. German military leaders insisted that Russian mobilization, even if directed only against Austria-Hungary, threatened Germany. Their war plans required attacking France first (through Belgium) before Russia could fully mobilize. Delay meant sacrificing the plan’s crucial timing advantage. On July 29, German Chief of Staff Moltke pressured Austria-Hungary to order general mobilization and urged immediate German mobilization. The military logic of mobilization timetables increasingly overwhelmed diplomatic efforts to localize the conflict.

Russia ordered general mobilization on July 30, partly because partial mobilization proved technically complicated and partly because intelligence suggested Austria-Hungary and Germany were mobilizing. This represented point of no return—Russian general mobilization meant war preparations against Germany, not just Austria-Hungary. Germany issued ultimatum demanding Russian demobilization within twelve hours. When Russia refused, Germany declared war on Russia on August 1.

France faced automatic alliance commitment to Russia. French leaders, determined to maintain the alliance that protected France from German power, ordered mobilization on August 1. Germany declared war on France on August 3. German implementation of the Schlieffen Plan required attacking France through Belgium, violating Belgian neutrality guaranteed by the 1839 Treaty of London to which Britain was signatory.

Britain’s entry was not automatic but became probable once Germany invaded Belgium. The violation of Belgian neutrality, combined with fear that German victory would create continental hegemon threatening British security, convinced the British Cabinet and Parliament to declare war on Germany on August 4. The British Expeditionary Force, though small, represented professional army that would play crucial role on the Western Front.

Within six weeks of the assassination, Europe’s great powers were at war. What might have remained limited Austro-Serbian conflict had cascaded through alliance commitments, mobilization imperatives, and strategic miscalculations into continental war involving all European great powers and their global colonial empires.

Major Alliances and Global Involvement

World War I quickly transcended European boundaries, becoming truly global conflict as imperial powers mobilized colonial resources and territories worldwide joined or were drawn into the fighting.

The Allied Powers: Coalition Against the Central Powers

The Allied Powers emerged from the pre-war Triple Entente but expanded dramatically during the war. The initial core consisted of France, Russia, and Britain, joined by Serbia (as the original conflict’s target) and Belgium (resisting German invasion). The Allied coalition’s strength lay in its combined resources, colonial empires providing manpower and materials, British naval dominance, and eventually American industrial might.

France entered the war determined to defend national territory and, many hoped, recover Alsace-Lorraine. French military doctrine emphasized offensive à outrance (attack to the utmost), believing that aggressive spirit and élan could overcome material disadvantages. This doctrine resulted in catastrophic casualties in the war’s opening months when French forces attacked German positions in Alsace-Lorraine while German forces swept through Belgium into France. Despite initial defeats, France mobilized its entire society for war, conscripting millions, converting industries to war production, and eventually stabilizing the Western Front.

Britain’s professional army—the British Expeditionary Force (BEF)—though small (approximately 100,000 troops initially), was highly trained and effective. The BEF fought crucial delaying actions at Mons and Le Cateau, helping to slow the German advance. Britain’s contribution grew enormously through volunteer recruitment (before conscription was introduced in 1916) and mobilization of imperial resources. Canadian, Australian, New Zealand, Indian, and other colonial forces made major contributions, particularly at Gallipoli, on the Western Front, in the Middle East, and in Africa.

Russia mobilized enormous armies—millions of peasant conscripts—but suffered from inadequate equipment, poor logistics, incompetent leadership, and technological backwardness. Initial Russian offensives into East Prussia and Galicia achieved some success before German and Austro-Hungarian counterattacks inflicted devastating defeats at Tannenberg and the Masurian Lakes. Russian forces achieved successes against Austria-Hungary but consistently lost to German forces. The combination of military defeats, economic collapse, and political dysfunction led to revolution in 1917 and eventual Russian withdrawal from the war.

Italy, though nominally a Triple Alliance member, remained neutral in 1914, claiming the alliance was defensive and that Austria-Hungary’s attack on Serbia didn’t trigger Italian obligations. The Allies, especially Britain and France, negotiated with Italy, promising territorial gains from Austria-Hungary through the secret 1915 Treaty of London. Italy entered the war against Austria-Hungary in May 1915 (though not against Germany until 1916), opening a new front in the Alps and along the Isonzo River. Italian military performance was mixed, suffering defeats like Caporetto (1917) but ultimately contributing to Austria-Hungary’s defeat.

Japan entered the war in August 1914, honoring its 1902 alliance with Britain but primarily pursuing its own imperial ambitions in East Asia and the Pacific. Japan seized German colonial possessions in China (including Qingdao) and German Pacific islands, expanding Japanese influence while European powers were distracted. Japanese naval forces assisted Allied operations in the Mediterranean and Indian Ocean. Japan’s participation shifted Asian power dynamics and would have significant post-war implications.

The United States remained neutral until April 1917, reflecting public opinion divided between immigrant communities maintaining Old World allegiances, anti-war progressives, and those sympathizing with Allied democracies against German autocracy. President Woodrow Wilson won re-election in 1916 campaigning as the candidate who “kept us out of war.” However, Germany’s unrestricted submarine warfare—sinking American ships and civilian vessels carrying Americans—generated public outrage. The Zimmermann Telegram (German proposal for Mexican-German alliance against the United States) further inflamed opinion. Wilson asked Congress for war declaration in April 1917, framing American intervention as crusade to “make the world safe for democracy.”

American entry transformed the war’s trajectory. The American Expeditionary Force, commanded by General John Pershing, grew to over 2 million troops in France by war’s end. American industrial production, agricultural exports, and financial resources sustained Allied war efforts. American intervention broke the Western Front stalemate, enabling offensives that finally defeated German forces in 1918.

Numerous smaller nations and colonial territories participated: Portugal, Romania, Greece, Belgium’s large Congo colony, British dominions (Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa), India, French colonial forces from Africa and Indochina, and others. This truly global conflict involved populations from every inhabited continent.

The Central Powers: Fighting on Multiple Fronts

The Central Powers—Germany, Austria-Hungary, Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria—coordinated militarily but faced strategic challenges of fighting on multiple fronts against enemies with superior combined resources.

Germany bore the primary military burden, fighting on Western and Eastern Fronts simultaneously while supporting weaker allies. German military excellence—superior tactics, training, and weaponry—enabled Germany to inflict consistently higher casualties than it suffered and to defeat Russia while holding Allied offensives on the Western Front. However, Germany faced crucial disadvantages: British naval blockade strangled German trade and caused civilian hardship; Germany’s allies were increasingly weak; and German resources were ultimately insufficient against Allied material superiority once America entered the war.

Austria-Hungary, the multinational empire whose Balkan ambitions triggered the war, proved a disappointing ally. Austro-Hungarian forces performed poorly against Russia and Serbia, requiring German intervention repeatedly. The empire’s internal nationalism problems worsened during the war as subject nationalities increasingly sought independence rather than supporting the imperial war effort. By 1918, Austria-Hungary was disintegrating internally even before military defeat.

The Ottoman Empire’s entry in November 1914 opened new fronts in the Caucasus (against Russia), Mesopotamia and Palestine (against Britain), and Gallipoli (against Allied invasion attempt). Ottoman forces, often underestimated by Allied planners, fought effectively, particularly at Gallipoli where they repulsed Allied landings. However, British-supported Arab revolt (1916-1918) and British campaigns captured Jerusalem, Baghdad, and Damascus, destroying Ottoman control over Arab territories. The empire’s economy collapsed under strain of total war, and Armenian Genocide (1915-1916) saw Ottoman authorities systematically murder an estimated 1-1.5 million Armenians—a horrific crime justified through wartime security concerns but representing genocidal ethnic cleansing.

Bulgaria joined the Central Powers in October 1915, attacking Serbia and enabling Austrian-German-Bulgarian forces to overrun Serbia and establish land connection to Ottoman Empire. Bulgarian forces fought on multiple fronts but by 1918 faced military collapse, signing armistice in September 1918 as the first Central Power to exit the war.

The Central Powers’ fundamental strategic problem was fighting a multi-front war of attrition against enemies with superior combined resources. German military excellence and interior lines enabling shifting forces between fronts delayed defeat but couldn’t overcome the Allies’ material advantages. Once American troops arrived in large numbers in 1918, Central Powers’ defeat became inevitable.

Trench Warfare and Technological Innovation

World War I introduced industrial-age warfare combining mass armies with modern technology, creating unprecedented destruction and military stalemate, particularly on the Western Front.

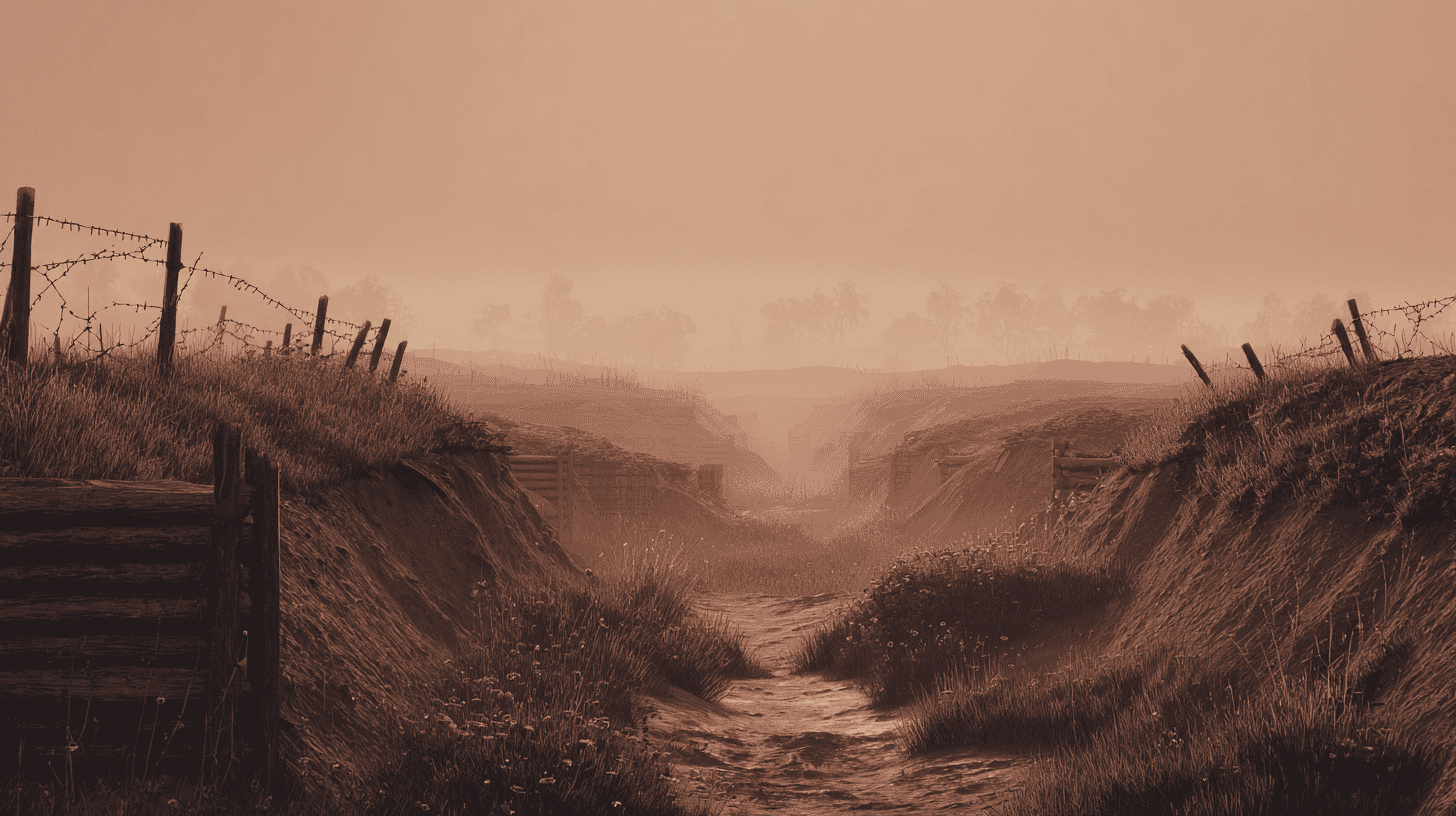

Trench warfare dominated the Western Front from late 1914 through 1918. After the war’s initial mobile phase—German advance through Belgium and France halted at the Marne (September 1914) and the subsequent “Race to the Sea” where both sides attempted to outflank each other—opposing armies dug elaborate trench systems stretching from the English Channel to Switzerland. These weren’t simple ditches but complex defensive networks including front-line trenches, support trenches, reserve trenches, communication trenches, underground bunkers, barbed wire entanglements, and artillery positions.

Life in the trenches was horrific. Soldiers endured constant artillery bombardment, sniper fire, trench raids, lice, rats, disease, and the ever-present stench of death and decay. “Trench foot” afflicted soldiers standing in waterlogged conditions. Shell shock (now recognized as post-traumatic stress disorder) broke thousands psychologically. Soldiers went “over the top” in suicidal charges across no-man’s-land toward enemy trenches, facing machine-gun fire and artillery that slaughtered attacking forces.

The tactical problem was breaking through enemy trenches to restore mobile warfare. Defensive firepower—particularly machine guns and artillery—made frontal attacks catastrophically costly. Major offensives like the Somme (1916, approximately 1 million casualties) and Verdun (1916, approximately 700,000 casualties) achieved minimal territorial gains at enormous cost. Commanders struggled to coordinate infantry, artillery, and emerging technologies effectively. Communications difficulties meant that even successful initial breakthroughs couldn’t be exploited before defenders rushed reserves to plug gaps.

Technological innovations attempted to overcome trench warfare’s deadlock:

Machine guns made infantry charges suicidal, as defensive positions could deliver devastating firepower. The British Vickers, German MG 08, and French Hotchkiss guns could fire hundreds of rounds per minute, creating killing zones that attacking infantry couldn’t cross. Machine-gun technology wasn’t new, but World War I demonstrated its defensive dominance.

Artillery advanced dramatically in range, accuracy, and destructive power. Heavy siege guns bombarded targets miles behind front lines. Artillery barrages preceding infantry attacks sometimes lasted days or weeks, attempting to destroy enemy defenses and cut barbed wire. However, artillery also churned battlefields into cratered moonscapes impassable to infantry and warned defenders of impending attacks. Artillery caused the majority of casualties—perhaps 60-70%—through high-explosive shells and shrapnel.

Poison gas, first used by Germans at Ypres (April 1915), represented chemical warfare’s horrific introduction. Chlorine, phosgene, and especially mustard gas caused agonizing injuries—suffocation, blindness, burned lungs, blistered skin. While gas masks reduced fatalities, gas created terror and psychological trauma. Both sides used chemical weapons extensively, though their tactical effectiveness remained limited. The horror of gas warfare led to post-war international prohibitions that largely (though not entirely) prevented its use in World War II.

Tanks, introduced by Britain in 1916, represented attempts to combine firepower, armor protection, and mobility to break through trenches. Early tanks were slow, mechanically unreliable, vulnerable to artillery, and uncomfortable for crews, but they demonstrated potential. By 1918, improved tank designs and tactics (particularly combined-arms operations coordinating tanks, infantry, artillery, and aircraft) helped break the trench stalemate.

Aircraft evolved rapidly from reconnaissance platforms to fighters, bombers, and ground-attack aircraft. Initially, planes observed enemy positions and directed artillery fire. Fighter aircraft developed to shoot down enemy reconnaissance planes, leading to aerial combat—”dogfights”—that captured public imagination. Strategic bombing began, with German Zeppelins and Gotha bombers attacking British cities, while Allied aircraft bombed German industrial targets. Close air support assisted ground forces. While aircraft’s direct military impact remained modest compared to artillery and infantry, they represented warfare’s future.

Submarine warfare revolutionized naval conflict. Submarines couldn’t challenge Allied surface fleets directly but threatened merchant shipping. Germany’s U-boat campaign aimed to starve Britain by sinking supply ships. Initially, submarines observed “cruiser rules” requiring stopping and searching merchant vessels before sinking them. However, Germany adopted “unrestricted submarine warfare” (announced January 1917) where U-boats sank ships without warning—a policy that brought America into the war but nearly succeeded in cutting Britain’s supplies. Allied countermeasures, particularly convoy systems and anti-submarine tactics, eventually contained the U-boat threat.

These technological changes made World War I the first truly industrial war—conflicts of material production where industrial capacity, resource mobilization, and technological innovation determined outcomes as much as battlefield courage or tactical brilliance.

Turning Points of the War

While World War I often appears as static deadlock punctuated by futile offensives, several crucial turning points shaped its outcome.

The Eastern Front Collapses: Russian Revolution and Withdrawal

Russia’s withdrawal from the war in 1917-1918 fundamentally altered the strategic balance, enabling Germany to transfer forces westward for final offensive attempts before American troops arrived in large numbers.

Military defeats, economic collapse, and political incompetence created revolutionary conditions in Russia. Tsarist autocracy proved incapable of managing total war’s demands. Military disasters—Tannenberg (1914), Gorlice-Tarnów (1915), Brusilov Offensive failures (1916)—cost millions of casualties. Supply failures left soldiers without ammunition, weapons, or food. The railway system collapsed under military and civilian demands. Urban populations faced food shortages and inflation. The regime’s corruption and incompetence became evident to all classes.

The February Revolution (March 1917 by Western calendar) overthrew Tsar Nicholas II, establishing a Provisional Government committed to continuing the war while implementing democratic reforms. However, the government’s determination to fulfill Russia’s alliance commitments and continue fighting—despite popular exhaustion and desire for peace—undermined its legitimacy. The Petrograd Soviet (workers’ and soldiers’ council) competed for authority, creating “dual power” situation where neither institution could govern effectively.

Vladimir Lenin’s Bolshevik Party, promising “peace, land, and bread,” seized power in the October Revolution (November 1917), overthrowing the Provisional Government. The Bolsheviks immediately sought peace with Germany, signing the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (March 1918) that ceded vast territories—Ukraine, Belarus, Baltic states, Caucasus regions—containing one-third of Russia’s population and agricultural land. These catastrophic territorial losses demonstrated Bolshevik desperation to exit the war and focus on consolidating power and fighting the emerging civil war.

Russia’s exit freed approximately 50 German divisions for transfer westward—the reinforcements that enabled Germany’s Spring 1918 offensives. However, the delay in moving these forces, combined with Germany’s need to occupy and exploit conquered eastern territories, meant the strategic benefit was less than anticipated. Moreover, Russia’s exit came just as American forces were arriving, replacing Russian military pressure with fresh American divisions.

U.S. Entry Into the War: The Decisive Intervention

American entry in April 1917 transformed the war from potential stalemate or negotiated settlement into Allied victory, though American impact took months to materialize fully.

Germany’s decision to resume unrestricted submarine warfare (suspended in 1916 after American protests) was calculated risk. German military leaders believed the U-boat campaign would starve Britain into surrender within six months—before American military intervention could become effective. They accepted that unrestricted submarine warfare would bring America into the war but calculated that American mobilization would take long enough that Britain would be defeated first.

This strategic calculation proved catastrophically wrong. The submarine campaign intensified but didn’t force British surrender. Meanwhile, American entry provided Allies with vast financial resources, industrial production, agricultural exports, and eventually millions of fresh troops. American loans to Britain and France prevented financial collapse. American grain exports fed Allied populations and armies. American industrial production provided munitions, weapons, and equipment.

The American Expeditionary Force mobilized slowly but decisively. The U.S. Army numbered only about 200,000 in 1917, mostly deployed in Western frontier posts or recent Mexican border operations. Creating mass army through conscription (Selective Service Act, May 1917), training recruits, transporting them across U-boat-threatened Atlantic, and integrating them with Allied operations required months. The first American troops arrived in summer 1917 but didn’t engage in major combat until spring 1918.

By summer 1918, American forces were arriving at 250,000 per month. The American Second Division helped stop German offensives at Château-Thierry and Belleau Wood (June 1918), demonstrating that fresh American troops could match German veterans. American forces played crucial roles in subsequent Allied offensives—particularly the Meuse-Argonne Offensive (September-November 1918), the war’s largest American battle involving 1.2 million U.S. troops.

American intervention was decisive not only militarily but psychologically and materially. German leaders recognized that American arrivals would shift the balance irreversibly against them, necessitating final offensive attempts in spring 1918 before American strength became overwhelming. When these offensives failed and Allied counteroffensives (supported by American troops) began pushing German forces back, German military leadership concluded the war was lost.

The Fall of the Central Powers: Collapse and Armistice

The Central Powers’ collapse in autumn 1918 was sudden and comprehensive, resulting from military defeats, economic exhaustion, domestic unrest, and recognition that continued fighting was futile.

Germany’s Spring 1918 offensives—Operation Michael and subsequent attacks—represented Germany’s last chance to win the war before American forces became decisive. These offensives achieved tactical success, breaking through Allied lines and advancing further than any offensive since 1914. However, they failed to achieve strategic breakthrough. Allied lines bent but didn’t break. German forces, though advancing, suffered heavy casualties they couldn’t replace. Logistics problems meant German troops couldn’t be supplied in their advanced positions.

The Allied counteroffensive beginning July 1918—the Hundred Days Offensive—pushed German forces back relentlessly. French, British, American, and Belgian forces attacked along the entire Western Front, employing improved combined-arms tactics coordinating infantry, tanks, artillery, and aircraft. German forces, exhausted and demoralized, retreated but maintained cohesion—the German Army wasn’t routed but recognized it couldn’t stop Allied advances indefinitely.

Bulgaria signed armistice on September 29, 1918, becoming the first Central Power to exit. Bulgarian military collapse opened Balkan routes toward Austria-Hungary and potentially Germany, threatening Central Powers’ strategic position.

The Ottoman Empire signed the Armistice of Mudros on October 30, 1918, after British forces had captured Jerusalem, Baghdad, and Damascus, destroying Ottoman control over Arab provinces. The empire was militarily defeated, economically exhausted, and politically disintegrating.

Austria-Hungary disintegrated from within before military defeat was complete. Nationalist movements in Czech, Slovak, Croatian, Slovenian, and other territories declared independence, establishing new nation-states. The multinational empire, held together by dynastic loyalty and imperial administration, fragmented as subject nationalities asserted self-determination. Austria-Hungary signed armistice with Italy on November 3, 1918, though by then the state was ceasing to exist.

Germany faced military defeat, naval mutiny, and revolutionary uprisings. The German Navy mutinied in Kiel (late October 1918) rather than sailing for suicidal final battle against the Royal Navy. Revolutionary councils formed in German cities. General Ludendorff, recognizing military defeat was inevitable, urged seeking armistice. Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicated on November 9, fleeing to Netherlands. The new German Republic’s representatives signed the armistice on November 11, 1918—the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month—ending the fighting.

The armistice terms were harsh: German forces evacuated occupied territories, Allied forces occupied German Rhineland, Germany surrendered war materials, and the naval blockade continued. These terms reflected Allied determination to ensure Germany couldn’t resume fighting and to establish conditions enabling eventual peace treaty enforcement.

The Aftermath of World War I

World War I’s consequences reshaped the twentieth century’s political, economic, social, and cultural landscape. Understanding these consequences reveals why the war’s impact extended far beyond 1918.

The Treaty of Versailles: A Punitive Peace

The Paris Peace Conference (1919) produced the Treaty of Versailles and other treaties restructuring post-war international order. Dominated by the “Big Three”—British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, French Premier Georges Clemenceau, and U.S. President Woodrow Wilson—the conference reflected competing visions for post-war order.

Wilson’s Fourteen Points proposed idealistic peace based on national self-determination, free trade, disarmament, open diplomacy, and creating the League of Nations to prevent future wars. Wilson believed that democratic, transparent international system could eliminate war’s causes. However, his vision clashed with Allied desires for security guarantees and territorial gains, and with the reality that implementing self-determination in ethnically mixed territories was practically impossible.

France, led by Clemenceau (“the Tiger”), demanded harsh terms ensuring Germany could never again threaten French security. French territory had suffered enormous destruction. Northern France was devastated battlefield. French casualties approached 1.4 million dead. French leaders demanded territorial guarantees, military restrictions on Germany, and reparations compensating war damages. French security required permanent German weakness.

Britain sought balance—punishing Germany sufficiently to satisfy public opinion demanding Germany “pay” for the war, but not so harshly as to create permanent German resentment or economic collapse that would undermine European recovery and British trade.

The resulting Treaty of Versailles (signed June 28, 1919—exactly five years after Franz Ferdinand’s assassination) imposed severe terms on Germany:

Article 231—the “war guilt clause”—forced Germany to accept sole responsibility for causing the war. This provision, intensely resented in Germany, justified subsequent punitive terms but became focus of German grievance and revisionist claims that Germany had been unfairly blamed.

Territorial losses stripped Germany of 13% of its European territory and 10% of its population. Alsace-Lorraine returned to France. The Polish Corridor and Upper Silesia went to recreated Poland, separating East Prussia from the rest of Germany. The Saar region came under League of Nations administration. All German colonies were distributed as League of Nations mandates to Allied powers. These losses, particularly the Polish Corridor dividing German territory, generated lasting resentment.

Military restrictions aimed to render Germany incapable of waging aggressive war: the army was limited to 100,000 volunteers, the navy to minimal forces without submarines or capital ships, air force and tanks were prohibited, the Rhineland was demilitarized, and Allied forces occupied the Rhineland for fifteen years. These restrictions eliminated Germany as military power but left Germans feeling defenseless and humiliated.

Reparations required Germany to compensate Allied war damages—a sum eventually set at 132 billion gold marks (approximately $33 billion, equivalent to hundreds of billions today). This enormous burden, far beyond Germany’s capacity to pay, created ongoing crises throughout the 1920s. German payments required earning foreign currency through exports, but reparations also required transferring physical goods, industrial equipment, coal, and other resources. The economic strain contributed to hyperinflation (1923), political instability, and lasting resentment.

The treaty excluded Germany from negotiations—it was presented as diktat (imposed settlement) rather than negotiated peace. German representatives were summoned to sign under threat of resumed war. This procedural humiliation compounded substantive grievances, feeding German perception that Versailles was unjust victor’s justice rather than fair peace.

The treaty’s harshness created what historian Margaret MacMillan called “the greatest failure of peacemaking in modern history.” While some historians argue the treaty wasn’t as severe as portrayed and that Germany retained capacity to recover, the critical point is that Germans across the political spectrum viewed Versailles as unjust humiliation—creating domestic consensus that treaty revision was legitimate national goal. This grievance was exploited by extremists, particularly Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party, who promised to overturn Versailles and restore German honor and power.

Collapse of Empires and Redrawing the Map

World War I destroyed four great empires—Russian, German, Austro-Hungarian, and Ottoman—fundamentally redrawing European and Middle Eastern political geography.

The Russian Empire collapsed into revolution and civil war, ultimately replaced by the Soviet Union. The Bolshevik Revolution created the world’s first communist state, committed to spreading revolution globally and fundamentally opposed to capitalist democracies. Soviet Russia represented ideological threat to the Western order, contributing to the ideological polarization characterizing much twentieth-century international politics. The Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania), Finland, and Poland achieved independence from Russian rule. The Russian Civil War (1917-1922) killed millions through combat, Red and White Terror, famine, and disease—creating trauma shaping Soviet political culture.

The German Empire became the Weimar Republic—Germany’s first democratic government, born from military defeat and burdened by Versailles treaty’s terms. The Weimar Republic faced enormous challenges: economic crisis, political polarization between communist and fascist extremes, French occupation of the Ruhr (1923) when Germany defaulted on reparations, hyperinflation destroying middle-class savings, and lack of democratic legitimacy among elites who associated democracy with defeat. While the republic stabilized temporarily in the mid-1920s, the Great Depression’s onset (1929) created conditions enabling Nazi rise to power.

The Austro-Hungarian Empire fragmented into multiple successor states: Austria and Hungary (both reduced to small nation-states), Czechoslovakia (combining Czech and Slovak territories), Yugoslavia (South Slav kingdom uniting Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes), with other territories transferred to Poland, Romania, and Italy. These new states faced challenges establishing viable governments, managing ethnic minorities, and achieving economic stability. The ethnic complexity of Central and Eastern Europe made creating ethnically homogeneous nation-states impossible—most successor states contained significant minorities, creating ongoing tensions.

The Ottoman Empire’s dismemberment created modern Middle Eastern political geography. The Treaty of Sèvres (1920), even harsher than Versailles, would have partitioned Anatolia among Greece, France, Italy, Britain, and an independent Armenia, reducing Turkey to a small state around Ankara. However, Turkish nationalist resistance led by Mustafa Kemal (Atatürk) defeated these plans through the Turkish War of Independence (1919-1923), resulting in the Treaty of Lausanne (1923) establishing modern Turkey’s borders.

Arab territories of the former Ottoman Empire were distributed as League of Nations mandates to Britain and France—nominally temporary arrangements preparing territories for independence but in practice colonial rule by different name. The Sykes-Picot Agreement (1916) had secretly divided Ottoman Arab territories into British and French spheres of influence, creating artificial borders that often divided ethnic and tribal groups while forcing diverse populations into single political units. These decisions created several ongoing conflicts and challenges:

The Palestine Mandate, assigned to Britain, faced contradictory commitments: the Balfour Declaration (1917) promised British support for a Jewish national home in Palestine, while Britain had also promised Arab independence in exchange for wartime support against Ottoman rule. Jewish immigration to Palestine increased dramatically, creating tensions with Palestinian Arabs and establishing foundations for the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Iraq, created by combining three Ottoman provinces (Mosul, Baghdad, Basra) with different ethnic and religious majorities (Kurdish, Sunni Arab, Shi’a Arab), faced persistent challenges establishing stable, inclusive governance—challenges continuing into the twenty-first century.

Syria and Lebanon came under French mandate. French authorities promoted sectarian divisions, particularly in Lebanon where they created confessional political system dividing power among religious communities—arrangements contributing to Lebanon’s civil war (1975-1990) and ongoing political dysfunction. Syria achieved independence in 1946 but experienced political instability, military coups, and eventually brutal civil war (beginning 2011).

The Kurdish people, promised potential autonomy in the Treaty of Sèvres, found themselves divided among Turkey, Iraq, Syria, and Iran by the Treaty of Lausanne and subsequent arrangements. Kurdish nationalism and demands for autonomy or independence have created ongoing conflicts in all four countries.

Saudi Arabia emerged from Arabian Peninsula power struggles, with Ibn Saud conquering most of the peninsula by 1932 and establishing the kingdom named for his family. Discovery of enormous oil reserves transformed Saudi Arabia into wealthy, influential state central to global energy markets.

These post-war territorial arrangements—created through combination of wartime secret agreements, peace conference negotiations, and local power struggles—established borders and political structures that often contradicted ethnic, tribal, and sectarian distributions. Many current Middle Eastern conflicts trace directly to World War I’s aftermath and the imperial powers’ decisions about post-Ottoman political geography.

Social and Economic Transformation

World War I fundamentally transformed societies, economies, and social structures in ways extending far beyond battlefield casualties.

Total war mobilization required comprehensive state control over economic and social life. Governments directed industrial production, allocated resources, controlled labor, rationed consumer goods, managed propaganda, and suppressed dissent. This expansion of state power didn’t fully reverse after the war—governments retained enhanced capacities and legitimacy for economic intervention and social management. The war established precedents for government economic planning, welfare programs, and social management that shaped twentieth-century political economy.

Women’s roles transformed dramatically. With millions of men mobilized for military service, women filled previously male-dominated occupations in munitions factories, transportation, agriculture, and offices. Women’s wartime contributions strengthened arguments for women’s suffrage—several nations (Britain in 1918, United States in 1920, Germany in 1919) extended voting rights to women during or shortly after the war. However, post-war period saw some rollback as returning soldiers reclaimed jobs and traditional gender expectations reasserted themselves. Nevertheless, the war permanently altered perceptions of women’s capabilities and legitimate social roles.

Labor movements strengthened through wartime full employment, government dependence on labor cooperation, and enhanced working-class political consciousness. Trade union membership expanded. Socialist and communist parties gained support, particularly as Russian Revolution demonstrated workers could overthrow capitalist systems. Labor unrest, strikes, and revolutionary movements swept Europe in 1918-1920, though most were suppressed or accommodated through reforms and concessions.

Economic devastation was immense. The war cost participating nations over $200 billion (in contemporary dollars, equivalent to trillions today). National debts soared. European nations shifted from creditors to debtors, while the United States emerged as dominant financial power. Physical destruction in combat zones—particularly northern France and Belgium—required enormous reconstruction investments. Agricultural and industrial production had been diverted to war needs, creating shortages and inflation. International trade and financial systems were disrupted, requiring years to reconstruct.

The 1920s economic instability—including German hyperinflation, French financial struggles with reconstruction costs and German reparations, and British economic difficulties—stemmed largely from war’s economic consequences. The war disrupted the pre-1914 economic globalization, creating fragmented economic blocs, protectionist policies, and currency instabilities. These problems contributed to the Great Depression’s severity and helped explain why economic crisis produced such catastrophic political consequences in Germany and elsewhere.

The “Lost Generation” of young men killed or disabled created demographic imbalances and cultural trauma. France lost 1.4 million dead (over 4% of total population), Britain approximately 900,000, Germany over 2 million, Russia possibly 3 million (exact figures are disputed), Austria-Hungary 1.1 million, Italy 600,000, and Ottoman Empire 700,000-800,000. These casualties fell disproportionately on young men of military age, creating gender imbalances, reducing birth rates, and depriving nations of an entire generation’s talents and productivity. The physical and psychological wounds of survivors—disabled veterans, shell-shock cases, gassed soldiers with ruined lungs—created ongoing social burdens.

Disillusionment and cultural trauma marked post-war societies. The optimism and nationalist enthusiasm of 1914 had been shattered by four years of industrial slaughter. Traditional authorities—political, religious, social—had led nations into catastrophe, undermining their legitimacy and wisdom. This disillusionment fostered artistic and intellectual movements challenging traditional forms and values (modernism, Dada, surrealism), political radicalization (both communist and fascist), and widespread cynicism about progress, rationality, and civilization itself.

Birth of the League of Nations

The League of Nations represented the first permanent international organization dedicated to maintaining peace, embodying Woodrow Wilson’s vision of collective security replacing balance-of-power politics. The League’s Covenant, incorporated into the peace treaties, committed members to: respecting territorial integrity and political independence, submitting disputes to arbitration or League consideration, applying economic and military sanctions against aggressors, and coordinating international cooperation on health, labor conditions, and other issues.

The League achieved some successes in resolving minor disputes, administering mandated territories, coordinating international health and labor organizations, and facilitating diplomatic communication. However, it ultimately failed to prevent World War II, revealing fundamental weaknesses:

Major powers were absent or marginalized. The United States never joined—despite Wilson’s central role in creating the League, the U.S. Senate rejected League membership, and subsequent Republican administrations avoided international commitments. Russia was excluded as revolutionary communist state until 1934. Germany was initially excluded as defeated enemy, joining only in 1926. Japan and Italy withdrew in the 1930s after pursuing aggressive policies. Britain and France, the League’s primary supporters, lacked commitment and resources to enforce collective security.

The League lacked enforcement mechanisms. It could recommend sanctions but couldn’t compel members to implement them. It had no military force to prevent aggression. When major powers challenged the international order—Japan invading Manchuria (1931), Italy invading Ethiopia (1935), Germany rearming and expanding (1933-1939)—the League proved impotent.

The League’s structure and procedures were cumbersome, requiring unanimity for major decisions, giving every member veto power, and making decisive action nearly impossible. The organization reflected the pre-war great power concert system more than genuinely new approach to international relations.

Despite these failures, the League established important precedents. It demonstrated that international organizations could coordinate global cooperation on technical issues (health, labor standards, refugees). It articulated principles of collective security, international law, and peaceful dispute resolution that influenced subsequent international relations. Most importantly, the League’s failures informed creation of the United Nations after World War II, which adopted similar goals with improved structures, broader membership, and greater powers.

Cultural Impact and Memory

World War I profoundly influenced literature, art, philosophy, and collective memory, creating cultural legacies that continue shaping how societies understand war, trauma, and modernity.

War literature captured the conflict’s horror, disillusionment, and trauma. Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front (1929) portrayed war’s brutality and meaninglessness through a young German soldier’s experiences, becoming the definitive anti-war novel. Wilfred Owen, Siegfried Sassoon, and other war poets wrote powerful verses capturing trench warfare’s horror and condemning the nationalist rhetoric that sent young men to die. Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms (1929) explored war’s senselessness and the collapse of meaning. Robert Graves’ Goodbye to All That (1929) offered bitter memoir of war experience and its aftermath.

These works shared common themes: the gap between patriotic rhetoric and battlefield reality, the mechanized horror of industrial warfare, the incompetence of military and political leaders, the lasting psychological trauma of combat, and the impossibility of communicating war experience to civilians. This literature shaped public memory, particularly in Britain and the Commonwealth, where World War I became symbol of futile sacrifice and lost generation.

Visual arts responded to war’s chaos and trauma through radical aesthetic innovations. The Dada movement, emerging in wartime Zurich, rejected traditional artistic forms and rational thought, embracing absurdity and nihilism as responses to civilization’s collapse into mechanized slaughter. Surrealism explored unconscious psychological depths, treating rationality with skepticism after rationalism had produced gas attacks and machine-gun massacres. German Expressionist artists like Otto Dix and George Grosz created disturbing images of war’s physical and psychological devastation. These artistic movements reflected broader cultural crisis—the sense that traditional forms, values, and assumptions had been discredited by the war.

War memorials and commemorations established collective memory practices. The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier—simultaneously honoring the individual sacrifice while acknowledging that industrialized warfare rendered many dead unidentifiable—became standard memorial form. The two-minute silence on November 11 at 11 AM annually commemorates the armistice moment. Poppies, inspired by John McCrae’s poem “In Flanders Fields,” became remembrance symbol. These rituals created shared commemorative practices shaping national identities and attitudes toward war, sacrifice, and memory.

Remembrance practices differed significantly across nations, reflecting different war experiences and political cultures. In Britain and Commonwealth countries, remembrance emphasized sacrifice, loss, and “never again” sentiment—World War I as tragic waste of young lives. In France, remembrance highlighted German aggression and French resilience, justifying vigilance against future German threats. In Germany, bitter debates contested whether the war had been lost through military defeat or civilian betrayal (the “stab-in-the-back” myth exploited by Nazis). In the United States, which suffered fewer casualties and fought for shorter duration, World War I occupied less central place in collective memory, overshadowed by World War II. These divergent memories shaped subsequent political cultures and attitudes toward international conflicts.

Conclusion: Understanding the Great War’s Enduring Relevance

World War I’s significance extends far beyond its immediate military and political consequences. The war represented a fundamental rupture in modern history—the moment when nineteenth-century optimism about progress, rationality, and civilization confronted the reality that industrial modernity could produce unprecedented destruction. The war destroyed empires, established new nations, redrew borders that continue shaping conflicts today, and demonstrated that modern warfare’s scale and horror exceeded anything previously imagined.

The war’s causes—nationalism, militarism, imperial rivalries, and rigid alliance systems—illustrated how interconnected international systems can transform local conflicts into catastrophic global wars. The assassination of an archduke in Sarajevo triggered world war not because the event itself was so significant but because the international system was structured to escalate rather than contain crises. Understanding these dynamics remains relevant for contemporary international relations, where alliance commitments, nationalist tensions, and military preparations continue shaping global security.

The war’s conduct introduced total war—mobilizing entire societies, targeting civilian populations through blockade and later aerial bombardment, using industrial technology for mass killing, and subordinating all social and economic activity to military victory. This pattern recurred in World War II and continues influencing how modern states prepare for and wage war. The technological innovations—tanks, aircraft, chemical weapons, submarines—established patterns of military development continuing through the twentieth century and into the twenty-first.

The peace settlement’s failures—particularly the Treaty of Versailles’ punitive terms and the artificial borders drawn through the Middle East—created resentments, conflicts, and instabilities that contributed directly to World War II and continue affecting contemporary geopolitics. The Israeli-Palestinian conflict, Kurdish nationalism, Iraqi instability, and Syrian civil war all trace partly to decisions made during and after World War I about how to organize post-Ottoman territories. The lesson that punitive peace settlements generate future conflicts rather than ensuring lasting peace remains relevant for contemporary conflict resolution.

The war’s social transformations—expanded state power, changed gender roles, labor movement strengthening, cultural disillusionment—shaped twentieth-century political, social, and cultural developments. The expansion of government economic management, welfare state development, and state surveillance all built on precedents established during World War I’s total mobilization. The war’s cultural trauma influenced modernist literature and art, existentialist philosophy, and broader skepticism about progress and rationality that characterized twentieth-century intellectual life.

Perhaps most significantly, World War I demonstrated the catastrophic consequences of political leaders miscalculating costs and benefits of war. In 1914, European leaders expected a short, decisive conflict. They didn’t anticipate four years of industrial slaughter, millions of casualties, economic ruin, social upheaval, and imperial collapse. This massive gap between expectations and reality stands as warning about overconfidence in military solutions, underestimation of war’s costs, and failure to appreciate how modern conflicts can spiral beyond control.

The war’s legacy continues shaping our world—in the borders dividing Middle Eastern nations, in the memories and commemorations marking November 11 annually, in the international institutions attempting to prevent future conflicts, and in the cultural understanding that modern warfare can threaten civilization itself. Understanding World War I—its causes, course, and consequences—remains essential for comprehending twentieth-century history and the contemporary international system built on the war’s ruins.

The Great War’s lessons about nationalism’s dangers, the risks of rigid alliance systems, the gap between military confidence and battlefield reality, and the catastrophic consequences of diplomatic failures remain urgently relevant for a world still grappling with territorial disputes, ethnic conflicts, and the ever-present possibility that regional crises can escalate into wider catastrophes.