Table of Contents

The Industrial Revolution: Technological Change and Its Global Impact

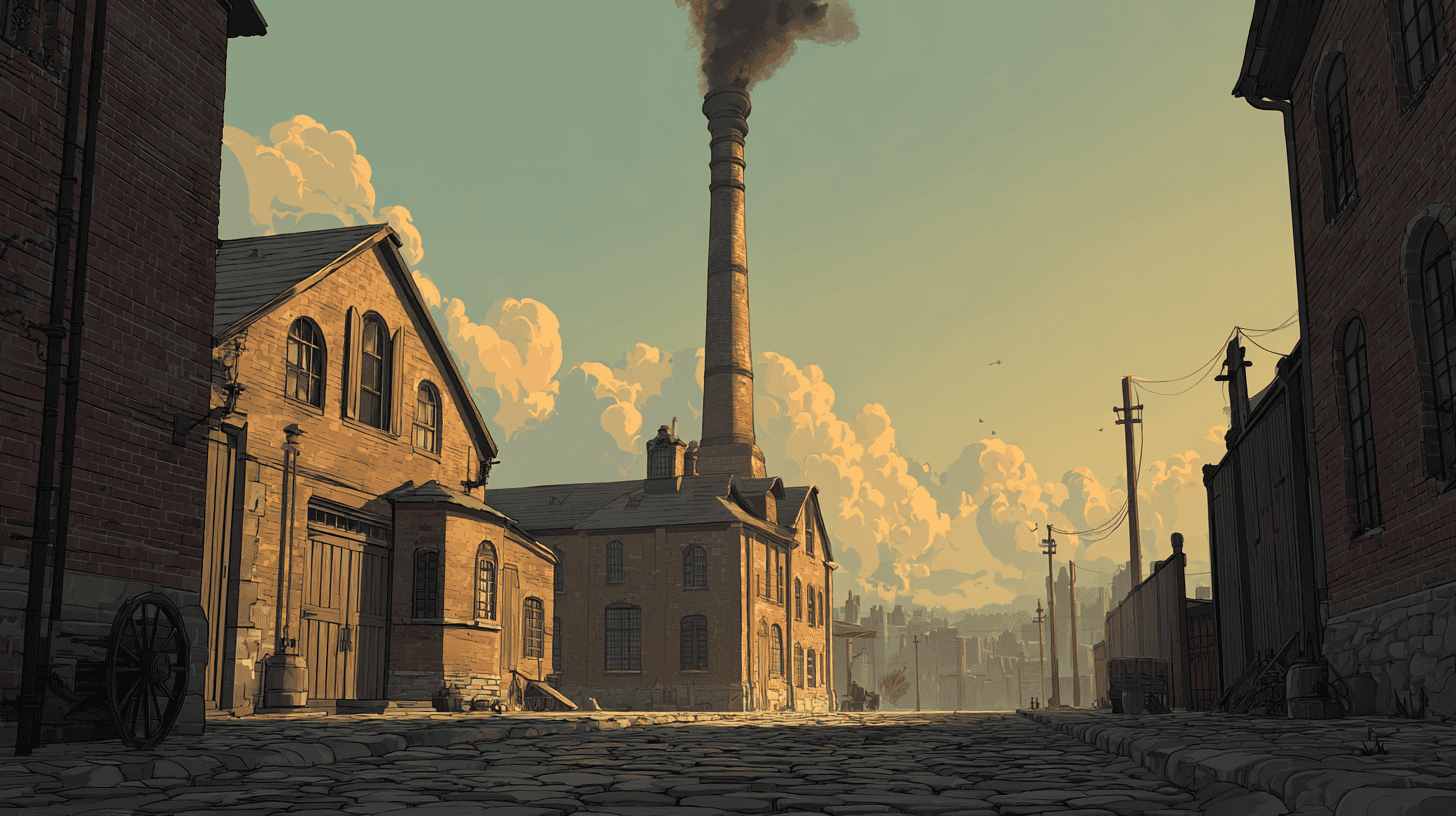

The Industrial Revolution represents one of history’s most dramatic transformations—a period when human societies fundamentally changed how they produced goods, organized labor, lived in communities, and interacted with the natural world. Beginning in Britain in the late 18th century and spreading globally over the next 150 years, this revolution moved humanity from millennia-old patterns of agricultural life and handicraft production to mechanized manufacturing, urbanization, and unprecedented economic growth.

The magnitude of this transformation cannot be overstated. Before the Industrial Revolution, most people lived much as their ancestors had for centuries: farming land, producing goods by hand, living in small villages, rarely traveling far from birthplaces, and experiencing little material improvement across generations. After industrialization, technological progress accelerated exponentially, living standards rose dramatically (though unevenly), populations exploded, cities grew to unprecedented sizes, and the pace of change became constant rather than exceptional.

Understanding the Industrial Revolution is essential not only for comprehending historical change but for making sense of the contemporary world. Modern capitalism, urbanization, environmental challenges, global trade networks, technological innovation, labor relations, and the vast disparities in wealth between industrialized and developing nations all trace their origins to this transformative period. The Industrial Revolution created the modern world—with all its prosperity and problems, its opportunities and inequalities, its remarkable achievements and daunting challenges.

This comprehensive examination explores why industrialization began where and when it did, what key innovations drove the transformation, how societies adapted (or failed to adapt) to revolutionary change, why the revolution spread unevenly across the globe, and what lasting legacies continue shaping the 21st century.

Why Britain? The Preconditions for Industrialization

The Industrial Revolution began in Britain—not in France, China, or other technologically sophisticated societies—for specific, identifiable reasons. Understanding these preconditions reveals that industrialization required a unique combination of factors rather than any single cause.

The Agricultural Revolution: Foundation for Industrial Change

Britain experienced an Agricultural Revolution in the 17th and 18th centuries that dramatically increased food production while requiring fewer agricultural workers—creating both the surplus population and the food supply necessary for industrialization.

Enclosure movement: Traditional open-field farming, where peasants cultivated scattered strips of land communally, gave way to enclosed private farms. Wealthy landowners consolidated holdings, fencing off land and implementing more efficient farming methods. While enclosure increased productivity, it displaced many small farmers who became available for industrial labor.

New farming techniques: Innovations transformed agriculture:

- Crop rotation systems (like the Norfolk four-course rotation) replaced leaving fields fallow, maintaining soil fertility while producing more food

- Selective breeding improved livestock, dramatically increasing meat and wool production

- New crops like turnips and clover provided winter animal feed, allowing year-round livestock maintenance

- Improved plowing and drainage techniques made previously unproductive land cultivable

Population growth: Agricultural improvements led to better nutrition and population increase. Britain’s population nearly doubled from about 5 million in 1700 to over 9 million by 1800, then exploded to 21 million by 1850. This growing population provided both workers for factories and consumers for manufactured goods.

Labor mobility: Displaced agricultural workers migrated to cities seeking employment. Unlike in many continental European countries where serfdom and rigid social structures prevented movement, British workers could relocate relatively freely.

Natural Resource Advantages

Britain possessed crucial natural resources in abundance and accessible locations:

Coal deposits: Britain had extensive coal reserves, often located near the surface and close to industrial centers. Coal provided the energy that powered steam engines, heated homes, and smelted iron. As industrialization progressed, coal mining itself became a massive industry employing hundreds of thousands.

Iron ore: High-quality iron ore deposits, often located near coalfields, supplied raw material for machinery, tools, rails, bridges, and structures. The proximity of coal and iron reduced transportation costs and accelerated industrial development.

Water power: Britain’s numerous rivers initially powered early textile mills before steam power became dominant. The transition from water to steam power freed industry from riverside locations.

Geographic advantages: As an island nation with excellent harbors and navigable rivers, Britain enjoyed easy internal transportation and global maritime access. No part of Britain lies far from the sea, facilitating trade and resource movement.

Political and Legal Factors

Britain’s political and legal systems encouraged entrepreneurship and innovation in ways many other societies did not:

Political stability: Following the Glorious Revolution (1688) and development of constitutional monarchy, Britain enjoyed relative political stability compared to continental Europe’s absolutist monarchies and revolutionary upheavals.

Property rights: Strong legal protections for private property gave entrepreneurs confidence to invest in long-term projects without fear of arbitrary confiscation.

Patent system: Britain’s patent laws, refined in the early 18th century, protected inventors’ rights and encouraged innovation by allowing inventors to profit from their creations. The 1624 Statute of Monopolies and subsequent patent legislation created frameworks for intellectual property protection.

Banking and finance: Britain developed sophisticated financial institutions—the Bank of England (founded 1694), stock markets, insurance companies, and commercial banks—that could mobilize capital for industrial investment. The ability to raise large sums through these institutions enabled expensive projects like railway construction.

Limited government regulation: Compared to continental European countries with guild systems and extensive economic regulations, Britain allowed relatively free economic activity. Entrepreneurs could start businesses without navigating complex guild restrictions.

Rule of law: An independent judiciary and rule of law protected contracts and business transactions, creating predictable environment for economic activity.

Cultural and Social Factors

Less tangible but equally important factors contributed to Britain’s industrial primacy:

Protestant work ethic: Some historians argue that Protestant values (particularly among Nonconformists like Quakers and Methodists) emphasized hard work, thrift, and worldly success in ways that encouraged entrepreneurship.

Scientific culture: The Scientific Revolution of the 17th century created intellectual climate valuing empirical observation, experimentation, and practical application of knowledge. The Royal Society (founded 1660) promoted scientific inquiry and practical innovation.

Literacy and education: While Britain wasn’t universally literate, enough people could read, write, and calculate to provide skilled workers and innovative engineers. Institutions like Dissenting Academies provided practical education when traditional universities emphasized classics over science.

Social mobility: While Britain had a rigid class system, more social mobility existed than in continental Europe. Successful entrepreneurs could gain social status, encouraging ambition and risk-taking.

Artisan tradition: Britain had strong traditions of skilled craftsmen—clockmakers, instrument makers, millwrights—whose mechanical expertise translated into industrial innovation. Many key inventors came from artisan backgrounds.

Colonial Trade and Markets

Britain’s expanding empire provided crucial advantages:

Raw materials: Colonies supplied cotton (from America and India), sugar (Caribbean), tobacco (America), and numerous other materials for British manufacturing

Markets: Colonies provided captive markets for British manufactured goods, particularly textiles

Capital accumulation: Profits from colonial trade, including the slave trade (tragically), provided capital for industrial investment

Global reach: Britain’s naval dominance and worldwide trading networks positioned it to dominate global commerce as industrialization increased production capacity

These factors combined to create unique conditions where industrialization could begin. No single factor explains why Britain industrialized first—rather, the convergence of agricultural change, natural resources, favorable institutions, cultural values, and global position created the necessary preconditions.

The First Wave: Textile Revolution and Steam Power

Britain’s Industrial Revolution began in the textile industry, where a cascade of innovations mechanized cloth production—humanity’s first experience with true machine-age manufacturing.

The Textile Industry: From Cottage to Factory

For centuries, textile production occurred through the “putting-out” or “domestic system”—merchants provided raw materials to rural families who spun thread and wove cloth at home, then returned finished goods for payment. This decentralized system limited production capacity and quality control.

Innovations in Spinning

The first breakthrough came in spinning—turning raw cotton or wool into thread:

The Spinning Jenny (1764): James Hargreaves invented a machine allowing one worker to spin multiple threads simultaneously (initially eight, later over 100). This dramatically increased productivity but still required human power and produced relatively weak thread suitable only for weft (horizontal threads).

The Water Frame (1769): Richard Arkwright developed a water-powered spinning machine producing stronger thread suitable for warp (vertical threads). The water frame required significant power, leading to its installation in mills built alongside rivers. This invention marked the transition from home production to factory system, as workers had to come to centralized locations where water-powered machinery operated.

The Spinning Mule (1779): Samuel Crompton combined features of the jenny and water frame, creating a “mule” that produced strong, fine thread suitable for high-quality cloth. The mule could be either hand-powered or mechanized, but eventually became the dominant spinning technology in factories.

These inventions increased spinning productivity so dramatically that they created bottlenecks in weaving—spinners could now produce more thread than handloom weavers could use.

Innovations in Weaving

The Power Loom (1785): Edmund Cartwright invented a mechanized loom, though early versions were unreliable. By the 1820s-1830s, improved power looms revolutionized weaving as they had spinning. A skilled handloom weaver might produce 20-30 yards of simple cloth weekly; a power loom operator could oversee machinery producing 200-300 yards.

The Cotton Gin (1793): Although invented by American Eli Whitney, this machine revolutionized cotton processing by efficiently separating seeds from cotton fiber. This dramatically reduced cotton prices and increased supply, fueling Britain’s textile industry. The cotton gin also tragically expanded American slavery as cotton production became enormously profitable.

The Rise of the Factory System

These innovations necessitated the factory system—centralized workplaces where workers operated machinery under supervision:

Organizational revolution: Factories represented not just technological change but organizational innovation. Owners could supervise workers, enforce discipline, coordinate complex production sequences, and achieve economies of scale impossible in domestic production.

Division of labor: Adam Smith described how dividing production into specialized tasks increased efficiency. Factories implemented this principle—workers performed narrow, repetitive tasks rather than crafting entire products.

Capital concentration: Building and equipping factories required substantial investment, leading to emergence of industrial capitalists who owned production means while workers owned only their labor.

Time discipline: Factory work required unprecedented time discipline. Unlike agricultural work paced by seasons and daylight, or craft work controlled by artisans themselves, factory work demanded regular hours and machine-paced labor. Workers had to arrive at specific times, work at machinery’s pace, and coordinate with others—transforming the very experience of work.

Early factories, particularly textile mills, became symbols of the new industrial age. Towns like Manchester, Birmingham, and Leeds grew from modest market towns into manufacturing giants.

Steam Power: The Universal Engine

While water power drove early textile mills, its limitations were clear: factories required riverside locations, faced seasonal water flow variations, and competed for limited waterpower sites. Steam power revolutionized industry by providing reliable, scalable, locationally flexible power.

James Watt and the Steam Engine

Steam engines existed before James Watt—Thomas Newcomen’s atmospheric engine (1712) pumped water from mines. However, Newcomen engines were inefficient, consuming vast amounts of coal and suitable only for stationary applications near coalfields.

Watt’s improvements (1760s-1780s):

- Separate condenser: Instead of cooling steam in the cylinder (wasting heat), Watt condensed steam in a separate chamber, dramatically improving efficiency

- Double-acting engine: Steam pushed the piston in both directions, doubling power output

- Rotary motion: Watt converted linear piston motion into rotary motion, allowing engines to drive machinery

- Governor mechanism: Automatic speed regulation maintained consistent power output

Partnership with Matthew Boulton: Watt partnered with industrialist Matthew Boulton, whose Birmingham factory manufactured steam engines. Their partnership combined technical innovation with business acumen, helping commercialize steam power.

Applications and Impact

Steam power transformed multiple industries:

Manufacturing: Steam engines powered factories, freeing them from riverside locations and allowing concentration in cities near labor and markets

Mining: More efficient steam pumps allowed deeper mining for coal and metals, providing resources that further fueled industrialization

Transportation: Steam powered railways and ships (discussed below), revolutionizing human mobility

Agriculture: Steam-powered threshing machines and other equipment mechanized farming

Steam power created positive feedback loops: coal powered steam engines, which pumped water from deeper coal mines, providing more coal for more steam engines. The Industrial Revolution became self-reinforcing, each innovation enabling others.

Iron and Steel: The Bones of Industry

Industrial expansion required vast quantities of iron—for machinery, tools, bridges, rails, ships, and structures. Innovations in iron production were thus crucial to industrialization.

Early Challenges

Traditional iron production used charcoal (from wood), but deforestation limited supply. Britain’s forests couldn’t provide enough charcoal for expanding iron industry.

Abraham Darby’s breakthrough (1709): Darby successfully smelted iron using coke (coal processed to remove impurities) instead of charcoal. This innovation unlocked coal’s potential for iron production, though it took decades for the process to spread widely.

Henry Cort’s innovations (1780s): Cort developed the puddling process and rolling mills, producing wrought iron (tougher than brittle cast iron) in quantity. These processes made iron suitable for a wider range of applications.

The Steel Revolution

Steel—iron combined with small amounts of carbon—is stronger and more versatile than iron but was expensive and difficult to produce in quantity until the mid-19th century.

The Bessemer Process (1856): Henry Bessemer developed a method to mass-produce steel by blowing air through molten iron, burning off impurities. This reduced steel production time from days to minutes and costs by 80-90%.

Open-hearth process (1860s): This complementary method allowed better quality control for steel production.

These innovations made steel abundant and affordable, enabling the Second Industrial Revolution’s massive infrastructure projects—skyscrapers, suspension bridges, steel ships, railways across continents.

Transportation Revolution: Shrinking Distance and Time

Perhaps no innovations affected daily life more dramatically than transportation improvements that shrank the world.

Railways: Iron Roads Transform Society

Railways represented industrialization’s most visible symbol and one of its most transformative technologies.

Early development: Primitive rail systems existed in mines for centuries. Richard Trevithick built the first steam locomotive (1804), but George Stephenson’s “Rocket” (1829) proved railways’ practical viability by winning the Rainhill Trials.

Railway mania: The 1830s-1840s saw explosive railway construction. The Stockton and Darlington Railway (1825) and Liverpool and Manchester Railway (1830) demonstrated railways’ potential. By 1850, Britain had 6,000 miles of track; by 1900, virtually every town had rail access.

Economic impact:

- Drastically reduced transportation costs, making goods cheaper and markets larger

- Created massive demand for iron, steel, coal, and labor

- Enabled businesses to reach national rather than local markets

- Facilitated labor mobility and urbanization

- Standardized time zones—before railways, each town kept its own local time; railways needed standardization

Social impact:

- Transformed travel from privilege of the wealthy to common experience

- Changed perceptions of distance and speed

- Separated work locations from residences more completely

- Created new suburbs as commuting became possible

- Inspired both enthusiasm and anxiety—some feared railway speeds were unhealthy

Railways became symbols of progress, appearing in art, literature, and popular consciousness as embodiments of modernity.

Steamships: Conquering the Oceans

Steam power also revolutionized maritime transportation:

Early steamships: Robert Fulton’s Clermont (1807) demonstrated steam navigation on the Hudson River. Early steamships supplemented sails with steam engines, primarily for rivers and coastal waters.

Transatlantic service: By the 1840s-1850s, steamships regularly crossed the Atlantic. The SS Great Western (1838) and SS Great Britain (1843), designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel, showed steam’s viability for ocean crossings.

Iron and steel hulls: Metal hulls allowed larger ships and made them more durable. Screw propellers replaced paddle wheels, improving efficiency.

Impact:

- Reduced transatlantic crossing from weeks to days

- Made shipping schedules reliable (not dependent on winds)

- Facilitated global trade and migration

- Enabled European colonial expansion

- United global markets more tightly

Communication Revolution: The Telegraph

The telegraph, invented in the 1830s-1840s with significant contributions from Samuel Morse, allowed near-instantaneous communication over long distances.

Impact:

- Coordinated railway systems and prevented accidents

- Enabled financial markets to operate in real-time

- Allowed newspapers to report current events rapidly

- Changed warfare by enabling quick military communication

- Laid groundwork for modern telecommunications

For the first time in human history, information could travel faster than people, fundamentally changing how businesses, governments, and societies operated. The Library of Congress preserves extensive documentation of these technological transformations and their impacts on American and global society.

The Social Transformation: New Ways of Living and Working

Industrialization didn’t just change how goods were produced—it transformed virtually every aspect of human life, from where people lived to how they worked, from family structures to class relations.

Urbanization: The Rise of Industrial Cities

One of the Industrial Revolution’s most visible impacts was rapid urbanization—the movement of populations from countryside to cities on a scale never before seen.

The Scale of Urban Growth

Cities grew explosively:

- Manchester: Population grew from about 25,000 in 1772 to over 300,000 by 1850

- Birmingham: Grew from 70,000 (1800) to 250,000 (1850)

- London: Already large, grew from 1 million (1800) to 6.7 million (1900)

- Glasgow: Grew from 77,000 (1801) to 762,000 (1901)

By 1851, more than half of Britain’s population lived in cities—the first nation in history where urban dwellers outnumbered rural ones.

Urban Conditions: Progress and Problems

Cities offered opportunities but created severe problems:

Housing crisis: Rapid growth outpaced housing construction. Working-class families crowded into:

- Back-to-back houses: Cheap, poorly ventilated structures sharing three walls with neighbors

- Tenements: Multi-family buildings with minimal space per family

- Cellars and garrets: The poorest lived in basements (often flooded) or attics

Families of six or more might occupy a single room. Multiple families shared outdoor privies. Overcrowding facilitated disease spread.

Sanitation catastrophe: Cities lacked infrastructure for their exploding populations:

- No sewage systems—waste dumped in streets or rivers

- Contaminated water supplies spread cholera, typhoid, and dysentery

- Industrial and human waste polluted rivers used for drinking water

- Smoke from thousands of coal fires created choking air pollution

Cholera epidemics (1832, 1848-1849, 1854, 1866) killed tens of thousands in Britain. Dr. John Snow’s discovery that cholera spread through contaminated water (1854) helped spur sanitation improvements, though progress was slow.

Crime and social disorder: Rapid growth created anonymity and social breakdown. Crime rates rose. Gin consumption reached epidemic levels in poor neighborhoods. Prostitution became widespread.

Class segregation: Cities developed stark class divisions. Wealthy industrialists lived in spacious suburbs with gardens; workers crowded into industrial districts shrouded in smoke. Friedrich Engels’s “The Condition of the Working Class in England” (1845) documented these horrific conditions.

Urban Reform and Improvement

Gradually, reforms addressed the worst conditions:

Public health acts: Legislation mandated improved water supplies, sewage systems, and housing standards

Urban planning: Some reformers promoted model communities like Saltaire or Port Sunlight—company towns with better housing and amenities

Parks movement: Public parks like London’s Victoria Park provided green spaces in industrial cities

Improved transportation: Omnibuses, trams, and railways enabled suburban development, reducing central city crowding

By the late 19th century, urban conditions were improving, though vast disparities persisted.

The Working-Class Experience: Life in the Factories

For those who worked in factories and mines, industrialization created a new and often brutal way of life fundamentally different from agricultural or artisan work.

Working Conditions

Long hours: Twelve to sixteen-hour days were common, six days per week. Some textile mills operated continuously with day and night shifts.

Low wages: Workers earned barely enough to survive. Women and children received even less—often 50-75% less than adult male wages for the same work.

Dangerous work: Factories lacked safety measures:

- Unguarded machinery caused horrific accidents—amputations, crushing injuries, deaths

- Textile workers inhaled cotton fibers, causing respiratory diseases

- Chemical exposure poisoned workers in emerging chemical industries

- Mine collapses, explosions, and toxic gases killed thousands of miners

Unhealthy environment:

- Poor ventilation and high temperatures

- Deafening noise from machinery

- Long hours standing on hard floors

- Exposure to toxic substances

Discipline and control: Factory owners enforced strict discipline:

- Fines for lateness, talking, or mistakes

- Physical punishment (especially for children)

- Dismissal without notice or recourse

- “Truck system” where workers received payment in vouchers redeemable only at company stores at inflated prices

Child Labor: The Darkest Aspect

Perhaps industrialization’s most horrifying aspect was extensive child labor exploitation.

Scale: Children as young as 5 or 6 worked in factories and mines. By some estimates, children made up one-third of factory workforces.

Why children? Employers valued children because:

- They accepted lower wages

- Small bodies could access tight spaces in machinery or mines

- They were more docile and easier to control than adults

- Growing populations provided abundant child labor supply

Conditions: Children worked the same long hours as adults in dangerous conditions:

- “Scavengers” in textile mills crawled under running machinery to collect loose cotton

- “Trappers” in mines sat in darkness for 12+ hours operating ventilation doors

- Children suffered stunted growth, deformities, and injuries

Gradual reform: Public outcry eventually produced protective legislation:

- Factory Act 1833: Limited children under 13 to 8-hour days

- Mines Act 1842: Prohibited women and children under 10 from underground work

- Factory Act 1847: Limited “young persons” and women to 10-hour days

- Education Act 1870: Established compulsory elementary education

These reforms came gradually and enforcement was inconsistent, but they marked recognition that industrialization’s human costs demanded limits.

The Changing Class Structure

Industrialization created new class divisions that replaced traditional rural hierarchies:

The Industrial Bourgeoisie

Factory owners, mine operators, railway magnates, and bankers formed a new wealthy class based on industrial capital rather than landed estates:

Values and lifestyle: The industrial bourgeoisie developed distinct values:

- Emphasis on hard work, thrift, and self-made success

- Victorian morality and respectability

- Philanthropy (often self-serving or paternalistic)

- Investment in education and culture

Political power: As they gained wealth, industrialists sought political power, challenging traditional aristocratic dominance. The Reform Acts (1832, 1867, 1884) gradually extended voting rights to middle-class men.

Conspicuous consumption: Successful industrialists built mansions, collected art, and displayed wealth, seeking social status to match economic power.

The Working Class

Industrial workers formed a new class defined by wage labor rather than land ownership or craft skills:

Proletarianization: Workers owned no capital—only their labor power, which they sold for wages. This dependence on employers created vulnerability.

Class consciousness: Living and working together in urban neighborhoods and factories, workers gradually developed class consciousness—awareness of shared interests distinct from employers’ interests.

Working-class culture: Distinctive culture developed:

- Mutual aid societies and friendly societies providing insurance against illness or death

- Music halls and public houses as entertainment

- Sports, especially football (soccer), became working-class passion

- Trade unions (discussed below) as collective organizations

The Middle Classes

Between wealthy industrialists and poor workers, expanding middle classes included:

- Shopkeepers and small business owners

- Clerks and office workers

- Teachers and civil servants

- Professionals like doctors and lawyers

Middle classes grew as industrial economies required more commercial and administrative labor. They often identified upward with the wealthy rather than downward with workers, creating complex class dynamics.

The Labor Movement: Workers Organize

Facing exploitation and danger, workers gradually organized to improve conditions through collective action—the labor movement.

Early Organization and Repression

Combination Acts (1799-1800): These laws prohibited workers from combining to demand higher wages or better conditions, treating unions as illegal conspiracies. Despite prohibition, secret organizing continued.

Luddites (1811-1816): Textile workers in northern England destroyed machinery they blamed for unemployment and low wages. The government responded with military force and executions. While dismissed as blindly opposing progress, Luddites recognized that technological change could harm workers if not accompanied by social protections.

Repeal of Combination Acts (1824): Unions became legal, though strikes remained restricted.

Growth of Trade Unions

Craft unions: Skilled workers organized first, forming unions based on specific trades (carpenters, printers, engineers). These “old model” unions were exclusive, well-organized, and focused on protecting skilled workers’ privileges.

General unions: In the 1880s-1890s, “new unionism” organized unskilled workers—dockers, gasworkers, transport workers. The London Dock Strike (1889) showed that even unskilled workers could organize effectively.

Achievements: Unions gradually won improvements:

- Higher wages and shorter hours

- Safer working conditions

- Grievance procedures

- Recognition as legitimate representatives of workers

Political action: The Labour Party, formed in 1900, gave workers direct political representation.

Strikes and Conflicts

Industrial disputes sometimes turned violent:

- Peterloo Massacre (1819): Cavalry charged a peaceful reform meeting in Manchester, killing 15

- Tolpuddle Martyrs (1834): Agricultural workers transported to Australia for forming a union

- Numerous strikes: Railway strikes, mining strikes, textile strikes—each testing workers’ collective power against employers and government

These conflicts slowly established workers’ rights to organize and negotiate collectively.

Changing Family and Gender Roles

Industrialization transformed family structures and gender relations:

Family Life

Separation of work and home: Unlike farming or domestic crafts where families worked together, factory work separated workplace and residence. Fathers (and often mothers) left home for long hours, reducing family time.

Child-rearing changes: With both parents working, children received less supervision. Factory work for young children removed them from parental authority and education.

Urban family size: Urban families gradually became smaller than rural ones as children became economic liabilities rather than assets in cities.

Women’s Roles

Factory work: Women worked in textile mills, clothing workshops, and other industries, usually for lower wages than men. Employers valued women as cheap, docile labor.

Domestic service: Enormous numbers of working-class women worked as domestic servants for middle and upper-class families—often their only employment option.

“Separate spheres” ideology: Middle-class Victorian values promoted “separate spheres”—men in public life and work, women in domestic life. This ideology didn’t match working-class reality where economic necessity forced women into paid labor.

Limited rights: Women lacked voting rights, property rights (married women’s property belonged to husbands), educational opportunities, and professional options. The women’s rights movement gradually challenged these restrictions, gaining momentum in the late 19th century.

Economic Transformation: The Rise of Industrial Capitalism

Industrialization created a new economic system—industrial capitalism—that operated according to different principles than agricultural or mercantilist economies.

Key Features of Industrial Capitalism

Private ownership: Individuals or corporations owned factories, mines, railways, and other productive assets

Wage labor: Most people worked for wages rather than owning productive property or farming their own land

Market competition: Businesses competed for customers, theoretically driving innovation and efficiency

Capital accumulation: Profit reinvestment in expanded production created economic growth

Division of labor: Specialized workers performed narrow tasks, increasing productivity

Monetary economy: Cash wages and purchases replaced barter and subsistence production

Banking and Finance

Industrial capitalism required sophisticated financial institutions:

Commercial banks: Provided short-term loans for business operations

Investment banks: Raised capital for large projects through bond and stock sales

Stock markets: Allowed trading of company ownership shares, mobilizing capital from many investors

Insurance companies: Reduced risks for businesses and individuals

Credit systems: Enabled purchases before payment, expanding consumption

These institutions mobilized savings for productive investment, channeling capital to its (theoretically) most efficient uses.

Business Organization

Joint-stock companies: These corporations allowed multiple investors to share ownership, profits, and risks—enabling projects requiring more capital than individuals could provide

Limited liability: Investors could lose only their investment amount, not their entire wealth, encouraging risk-taking

Professional management: As businesses grew larger, ownership and management separated. Professional managers ran companies on behalf of shareholders.

Vertical integration: Some companies controlled multiple production stages—raw material extraction, manufacturing, distribution

Horizontal integration: Other companies dominated single stages across multiple locations, achieving economies of scale

Economic Growth and Business Cycles

Industrialization produced unprecedented sustained economic growth—GDP per capita rose continuously rather than remaining static as in previous centuries.

However, industrial economies experienced business cycles—recurring patterns of expansion and contraction:

Boom periods: High investment, increasing production, rising employment, optimism

Financial crises: Overinvestment, speculation, or external shocks triggered panic

Recessions/depressions: Business failures, unemployment, falling prices, pessimism

Recovery: Gradual return to growth

Major depressions occurred in the 1840s, 1870s-1890s (the “Long Depression”), and 1930s, causing widespread suffering and raising questions about capitalism’s stability.

Economic Theories and Debates

Industrialization sparked new economic thinking:

Classical economics (Adam Smith, David Ricardo): Argued that free markets, competition, and self-interest produced optimal outcomes. Governments should interfere minimally, allowing “invisible hand” to allocate resources efficiently.

Marxism (Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels): Argued that capitalism inevitably exploited workers, concentrated wealth, and would ultimately collapse through its internal contradictions. Predicted workers would overthrow capitalism and establish socialism.

Utopian socialism (Robert Owen, Charles Fourier): Proposed alternative communities based on cooperation rather than competition. Some industrialists like Owen experimented with model communities offering better wages and conditions.

Reform movements: Others argued capitalism needed regulation to address market failures, protect workers, and ensure fairness.

These debates continue today in different forms—how much should markets be regulated? What responsibilities do businesses have to workers and communities? Can capitalism be reformed or must it be replaced?

The Global Spread: Industrialization Beyond Britain

While Britain industrialized first, industrialization eventually spread globally—though unevenly, at different paces, and with varying consequences.

Continental Europe: Following Britain’s Path

Belgium: The first European nation to industrialize (1820s-1830s), benefiting from coal resources, proximity to Britain, and limited government interference

Germany: United Germany (1871) industrialized rapidly in the late 19th century, eventually surpassing Britain in steel production and chemical industries. German industrialization featured:

- Strong government support and planning

- Close bank-industry relationships

- Advanced technical education

- Rapid adoption of new technologies

- Emphasis on heavy industry and chemicals

France: Industrialized more gradually, maintaining stronger agricultural sector. French industrialization emphasized luxury goods and skilled craftsmanship alongside heavy industry.

Other nations: Netherlands, Switzerland, Sweden, and other nations industrialized at varying paces, each adapting the process to local conditions.

The United States: A Rising Industrial Giant

Natural advantages: The United States possessed enormous natural resources—coal, iron ore, oil, timber, fertile farmland—spread across vast territory

Technological adoption: Americans eagerly adopted British technologies and developed their own innovations

Transportation revolution: Canals, railways, and steamboats unified the large nation economically. The transcontinental railroad (1869) connected coasts.

Immigration: Massive immigration provided labor for factories, mines, and construction. Between 1840 and 1914, over 30 million immigrants entered the U.S.

American System of Manufacturing: The U.S. pioneered interchangeable parts and assembly line production, reaching fullest expression in Henry Ford’s automobile factories

Size and scale: By 1900, the United States was the world’s largest industrial economy, surpassing Britain. American industrial production emphasized mass production and standardization.

Regional differences: Northern industrialization contrasted with Southern agricultural economy based on cotton and (until 1865) slavery. The Civil War (1861-1865) ensured Northern industrial capitalism’s victory over Southern plantation system.

Japan: Non-Western Industrialization

Meiji Restoration (1868): Japan’s new government determined to modernize rapidly to avoid colonization. The slogan “rich country, strong army” captured the program’s essence.

Government-led industrialization: Unlike Western industrialization driven by private entrepreneurs, Japanese government actively directed industrialization:

- Built model factories and shipyards

- Sent students abroad to learn Western techniques

- Hired foreign experts to transfer knowledge

- Promoted specific industries through subsidies and protection

Selective adoption: Japan adopted Western technology while maintaining many traditional cultural elements, showing industrialization didn’t require complete Westernization

Rapid success: By the early 20th century, Japan defeated Russia in war (1904-1905), shocking the world and demonstrating industrial power. Japan became the first non-Western industrial nation.

Russia: Late and Incomplete Industrialization

Late start: Russia began significant industrialization only in the 1890s under Finance Minister Sergei Witte

State direction: The czarist government built railways, promoted industries, and attracted foreign investment

Uneven development: Modern factories and railways coexisted with vast peasant agriculture and feudal-like conditions

Social tensions: Rapid industrialization without political reform created explosive tensions contributing to the 1917 Revolution

Latin America, Africa, and Asia: Limited Industrialization

Most of the world industrialized slowly or not at all during the 19th century:

Colonial relationships: European colonial powers often prevented colonized territories from industrializing, wanting them to remain suppliers of raw materials and consumers of European manufactured goods

Economic dependency: Even independent nations like those in Latin America became economically dependent on exporting raw materials (minerals, agricultural products) and importing manufactures—perpetuating underdevelopment

Lack of preconditions: Many regions lacked the capital, technology, institutions, infrastructure, or political stability necessary for industrialization

China and India: Two historic manufacturing centers were actually de-industrialized—British competition destroyed traditional industries like Indian textile production. Both became primarily agricultural exporters.

This uneven development created the global economic hierarchy persisting today—wealthy industrialized nations (the “Global North”) and poorer developing nations (the “Global South”).

Intellectual and Cultural Responses

Industrialization sparked intense intellectual and cultural responses as thinkers, artists, and writers grappled with unprecedented social transformation.

Literature and Art

Romantic reaction: Romantic poets and artists often criticized industrialization:

- William Blake’s “dark Satanic mills”

- William Wordsworth’s concerns about urban growth

- John Constable’s idealized rural landscapes

- Pre-Raphaelite rejection of industrial aesthetics

Social realism: Writers documented industrial conditions:

- Charles Dickens portrayed urban poverty, exploitation, and social problems in novels like “Hard Times” and “Oliver Twist”

- Elizabeth Gaskell’s “North and South” examined class conflicts in industrial Manchester

- Victor Hugo and Émile Zola depicted working-class life in France

- American writers like Upton Sinclair exposed industrial abuses

Arts and Crafts movement: William Morris and others promoted traditional craftsmanship against mass production, though their handmade goods were too expensive for most people

Political Ideologies

Industrialization sparked competing visions of society’s future:

Liberalism: Emphasized individual freedom, free markets, limited government, and gradual reform through democratic processes

Conservatism: Defended tradition, hierarchy, and gradual change while opposing radical transformation

Socialism: Advocated collective ownership of production means and more equal distribution of wealth. Many varieties existed from revolutionary Marxism to democratic socialism to utopian communities

Anarchism: Rejected all forms of coercive authority, seeking voluntary cooperation

These ideologies competed throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, shaping politics globally.

Social Reform Movements

Evangelical Christianity: Many British reformers drew motivation from religious conviction:

- William Wilberforce’s antislavery campaign

- Lord Shaftesbury’s factory reform efforts

- Salvation Army’s work among the urban poor

Utilitarianism: Jeremy Bentham and followers promoted reform based on “the greatest happiness for the greatest number”

Settlement house movement: Middle-class reformers lived in poor neighborhoods providing education, healthcare, and assistance

Cooperative movement: Workers formed cooperatives—collectively owned businesses that shared profits

Temperance movement: Reformers combated alcoholism, which devastated many working-class families

Environmental Consequences: The Ecological Cost of Industrialization

Industrialization’s environmental impact became one of its most lasting and troubling legacies.

Air Pollution

Coal smoke: Burning millions of tons of coal created horrific air pollution:

- London’s “pea-souper” fogs were actually smog—smoke plus fog

- Respiratory diseases plagued industrial cities

- Acid rain damaged buildings and vegetation

- Soot blackened everything—buildings, clothing, lungs

Some pollution episodes were deadly—London’s Great Smog (1952) killed thousands, finally spurring clean air legislation.

Water Pollution

Industrial waste: Factories dumped chemical waste, dyes, and toxic substances into rivers

Human sewage: Growing cities overwhelmed water systems

Consequences:

- Rivers became open sewers—London’s Thames was biologically dead

- Groundwater contamination

- Disease spread through contaminated water

Deforestation

Timber demand: Building, shipbuilding, and charcoal production (before coal) stripped forests

Land clearing: Agriculture expanded to feed growing populations

Consequences: Erosion, habitat loss, local climate changes

Resource Depletion

Mining: Extraction of coal, iron ore, copper, and other minerals created:

- Landscape destruction

- Waste heaps

- Subsidence

- Water table disruption

Unsustainable extraction: Resources were treated as infinite rather than carefully managed

Climate Change

Carbon emissions: Burning fossil fuels released carbon dioxide, beginning the buildup of greenhouse gases causing climate change—though this wasn’t recognized until the mid-20th century

Cumulative impact: Two centuries of industrialization have dramatically altered Earth’s atmosphere and climate

The Industrial Revolution began humanity’s transformation from a species living within natural cycles to one capable of altering the entire planet’s systems—a shift whose consequences we’re still reckoning with.

The Second Industrial Revolution (1870-1914)

The late 19th and early 20th centuries witnessed a Second Industrial Revolution—new technologies, industries, and economic organization that accelerated the first revolution’s transformations.

New Energy Sources

Electricity: Perhaps the era’s most transformative technology:

- Thomas Edison’s incandescent light bulb and power distribution system

- Nikola Tesla’s alternating current systems

- Electric motors replaced steam engines in factories, making production more flexible

- Electric lighting extended productive hours and improved urban life

- Electric streetcars and subways revolutionized urban transportation

Petroleum: Oil became crucial for:

- Internal combustion engines (automobiles, tractors, trucks)

- Heating and lighting

- Industrial processes

- Would become 20th century’s most important energy source

Chemical Industries

Synthetic dyes: German chemical industry developed artificial dyes, revolutionizing textile industry and establishing Germany’s chemical dominance

Fertilizers: Synthetic fertilizers increased agricultural productivity, supporting growing populations

Pharmaceuticals: New drugs like aspirin improved health

Plastics: Early plastics like Bakelite began replacing natural materials

Explosives: Alfred Nobel’s dynamite aided construction but also enhanced warfare’s destructiveness

Communication and Information

Telephone: Alexander Graham Bell’s invention (1876) enabled voice communication over distance

Radio: Guglielmo Marconi’s wireless telegraphy led to radio broadcasting

Motion pictures: The Lumière brothers and others created cinema, a new entertainment and communication medium

Mass media: Cheap newspapers, magazines, and books spread information to mass audiences

Transportation Advances

Automobiles: Karl Benz and others developed gasoline-powered automobiles (1880s-1890s). Henry Ford’s Model T (1908) made cars affordable for middle-class consumers through assembly line production

Airplanes: Wright brothers’ first flight (1903) began aviation age

Improved ships: Steel hulls, steam turbines, and oil fuel created faster, larger, more efficient ships

Mass Production and Scientific Management

Taylorism: Frederick Taylor’s “scientific management” analyzed and optimized work processes, increasing efficiency but also intensifying labor

Assembly lines: Henry Ford’s moving assembly line (1913) epitomized mass production—breaking complex processes into simple repetitive tasks performed by workers stationed along the line

Standardization: Interchangeable parts and standardized designs enabled mass production and repair

New Business Organization

Corporations: Large corporations with thousands of employees and operations across multiple locations became dominant

Monopolies and trusts: Companies like Standard Oil, U.S. Steel, and American Tobacco controlled entire industries, raising concerns about competition

Antitrust legislation: Governments attempted to regulate monopolies through laws like the Sherman Antitrust Act (1890)

Multinational corporations: Businesses operated across national boundaries, beginning economic globalization

Globalization

The Second Industrial Revolution accelerated global economic integration:

Trade expansion: Steamships and railways moved goods globally

Investment flows: European and American capital financed development worldwide

Migration: Tens of millions migrated from Europe to Americas, Russia, and elsewhere

Communication networks: Telegraph cables and later radio connected continents

Imperialism: Industrial nations seized colonies for resources and markets, with technology enabling domination

Long-Term Consequences and Modern Legacy

The Industrial Revolution’s impacts extend far beyond the 19th century, shaping the contemporary world in profound ways.

Economic Development Patterns

The Great Divergence: Industrialization created enormous wealth gaps between industrial and non-industrial societies that persist today. In 1800, living standards globally were relatively similar; by 1900, industrialized nations were vastly wealthier.

Development challenges: Nations that didn’t industrialize early face difficult development paths, competing against established industrial powers

Economic growth paradigm: Industrialization established continuous economic growth as normal expectation—a historically unprecedented pattern

Technological Acceleration

Industrialization began humanity’s technological acceleration—the increasingly rapid pace of innovation:

- Thousands of years passed between agriculture’s invention and steam power

- Decades between steam and electricity

- Years between major computing advances

This acceleration continues, creating both opportunities and disorientation.

Environmental Crisis

Climate change: Industrial carbon emissions are primary cause of global warming, the century’s defining challenge

Pollution: Air, water, and soil pollution remain serious problems

Resource depletion: Many resources are being depleted faster than they can regenerate

Biodiversity loss: Industrial expansion contributes to species extinction

Addressing these issues requires rethinking industrialization’s assumptions about unlimited growth and resource exploitation.

Urbanization

Global urban majority: As of 2008, more humans live in cities than rural areas—culmination of urbanization beginning in Industrial Revolution

Megacities: Cities of 10+ million inhabitants create unprecedented challenges and opportunities

Urban design: Contemporary urban planning still grapples with problems industrialization created

Labor and Work

Modern labor rights: Contemporary labor laws, working hours, minimum wages, and safety regulations emerged from industrial-era struggles

Automation concerns: Today’s automation and AI debates echo 19th-century Luddite concerns about technology displacing workers

Gig economy: New forms of precarious labor raise questions similar to early industrial exploitation

Social Inequality

Wealth concentration: Industrial capitalism created enormous wealth disparities that remain contentious

Class divisions: While terminology has changed, class conflicts rooted in industrialization persist

Social mobility: Industrial society promised (and sometimes delivered) opportunity for upward mobility, but also created new forms of stratification

Democratic Development

Expanded suffrage: Industrial working classes eventually gained political rights, expanding democracy

Social welfare: Modern welfare states developed partly in response to industrialization’s social costs

Labor movements: Trade unions and labor parties remain important political forces

Global Interdependence

Industrialization began economic globalization that defines the contemporary world:

- International supply chains

- Global financial markets

- Transnational corporations

- Migration flows

- Cultural exchange

This interdependence creates both opportunity and vulnerability.

Conclusion

The Industrial Revolution represents one of history’s great dividing lines—before and after are simply different worlds. The transformation from agricultural, handcraft, rural societies to industrial, mechanized, urban ones occurred with breathtaking speed, creating the modern world with all its complexity, contradictions, opportunities, and challenges.

The revolution began with textile machinery and steam engines in 18th-century Britain but cascaded across two centuries and the entire globe, transforming how humans produce goods, organize work, live together, communicate across distances, move through space, distribute wealth, wield power, and interact with the natural world. No aspect of human life remained untouched.

The Industrial Revolution’s benefits were real and substantial—higher living standards, longer lifespans, reduced physical drudgery, expanded opportunities, technological marvels, and material abundance that previous generations couldn’t imagine. Industrial capacity defeated fascism in World War II, enabled modern medicine, sent humans to space, connected the world through communication networks, and lifted billions from poverty.

Yet the costs were also profound—environmental devastation, brutal working conditions, child exploitation, social disruption, inequality, colonialism, and the creation of weapons capable of destroying civilization. The dark Satanic mills William Blake condemned weren’t merely poetic metaphor but lived reality for millions whose labor built industrial society.

Understanding the Industrial Revolution means grappling with this duality. It wasn’t simply progress or disaster but both simultaneously—a transformation that created unprecedented prosperity while extracting enormous human and environmental costs, that expanded human capabilities while creating new vulnerabilities, that liberated some while exploiting others.

The Industrial Revolution’s fundamental patterns persist: technological change disrupts economies and societies; economic growth creates both winners and losers; innovation enables progress but creates unforeseen consequences; regulatory frameworks lag behind technological change; environmental impacts accumulate over generations; global inequality reflects historical development patterns.

As the 21st century confronts challenges from climate change to artificial intelligence, from persistent inequality to resource constraints, understanding the Industrial Revolution provides crucial historical perspective. The decisions made by industrializing societies—what to prioritize, how to distribute costs and benefits, what regulations to implement, how to balance growth against sustainability—created the world we inhabit. The decisions we make about today’s transformative technologies—digital technology, biotechnology, renewable energy—will similarly shape the future.

The Industrial Revolution teaches that technological change is inevitable but its social implications are choices. Societies can harness innovation for broad benefit or allow it to concentrate wealth and power. They can mitigate negative consequences or ignore them until crisis forces action. They can include diverse voices in shaping change or allow narrow interests to dominate.

More than two centuries after it began, the Industrial Revolution continues—not as historical artifact but as ongoing transformation. We remain an industrial civilization, our prosperity built on fossil fuels, mechanized production, and technological innovation. Whether we can transition to sustainable, equitable, ecologically sound prosperity while preserving industrialization’s genuine achievements remains humanity’s great challenge. Understanding how we arrived at this moment—through the Industrial Revolution’s triumphs and tragedies—is essential for navigating the future wisely.